A Policy Analysis Based on the Network Readiness Index 2025

Executive Summary

The Network Readiness Index (NRI) 2025 by the Portulans Institute and published recently just this week, presents a paradoxical but instructive portrait of the Philippines’ digital transformation.

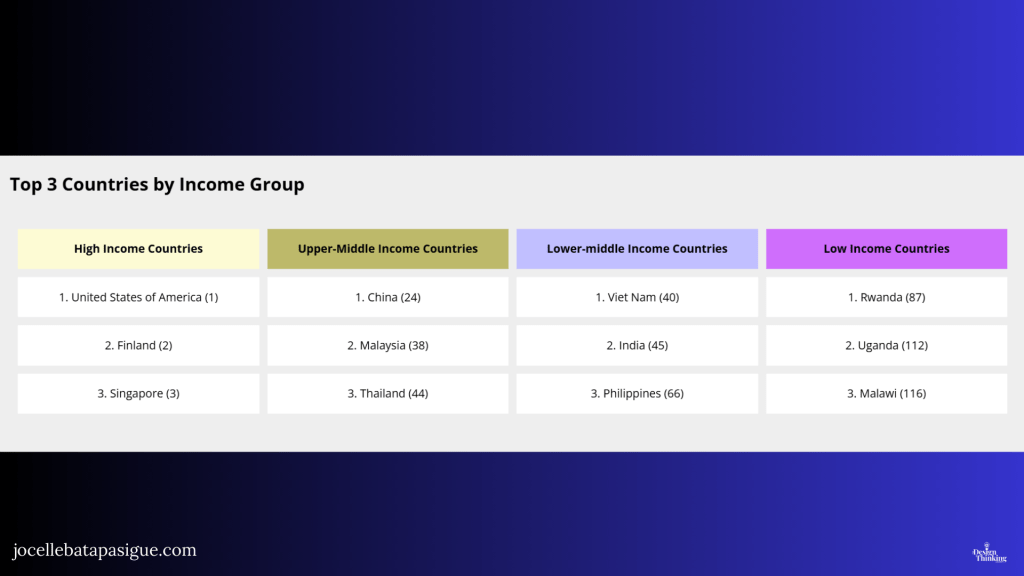

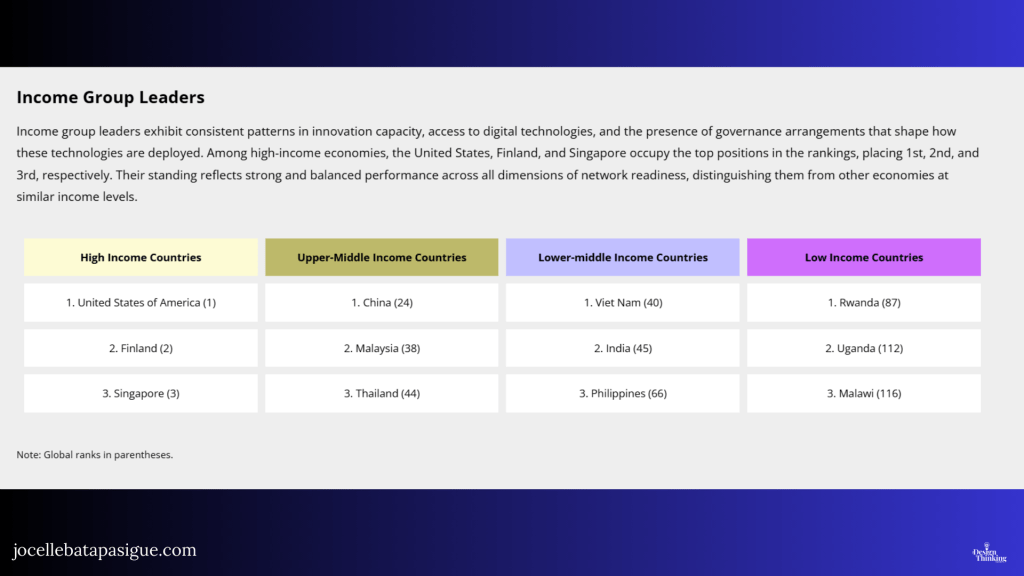

The Philippines ranks third among lower-middle-income economies in the Network Readiness Index 2025, alongside Viet Nam and India, confirming that it performs above what its income level would predict. This position reflects strong fundamentals—particularly high digital engagement among individuals, widespread mobile connectivity, and a digitally active population. In other words, the Philippines is not digitally lagging in terms of access or basic adoption, and its people are largely ready to participate in the digital economy.

Other top performers across income groups illustrate how different policy choices drive digital readiness. Among high-income economies, the United States of America, Finland, and Singapore consistently lead, combining advanced technology ecosystems with strong governance and high societal impact. In the upper-middle-income group, China, Malaysia, and Thailand demonstrate how scale, industrial policy, and targeted digital investments can accelerate readiness even without high-income status.

Within the lower-middle-income group, the Philippines’ closest peers are Viet Nam and India, both of which rank slightly ahead due to stronger performance in business adoption, manufacturing-linked digitalization, or innovation scale. Meanwhile, low-income leaders such as Rwanda, Uganda, and Malawi show that purposeful policy focus can still yield digital progress under resource constraints. Taken together, these examples reinforce a core NRI insight: digital leadership is shaped less by income level than by governance quality, institutional execution, and commitment to inclusion.

The country ranks 66th out of 127 economies, placing it firmly among lower-middle-income digital out-performers—economies that achieve higher levels of digital readiness than their income level would ordinarily predict. Yet behind this relative success lies a set of structural weaknesses that, if unaddressed, will constrain the Philippines’ ability to translate digital progress into inclusive and sustainable national development.

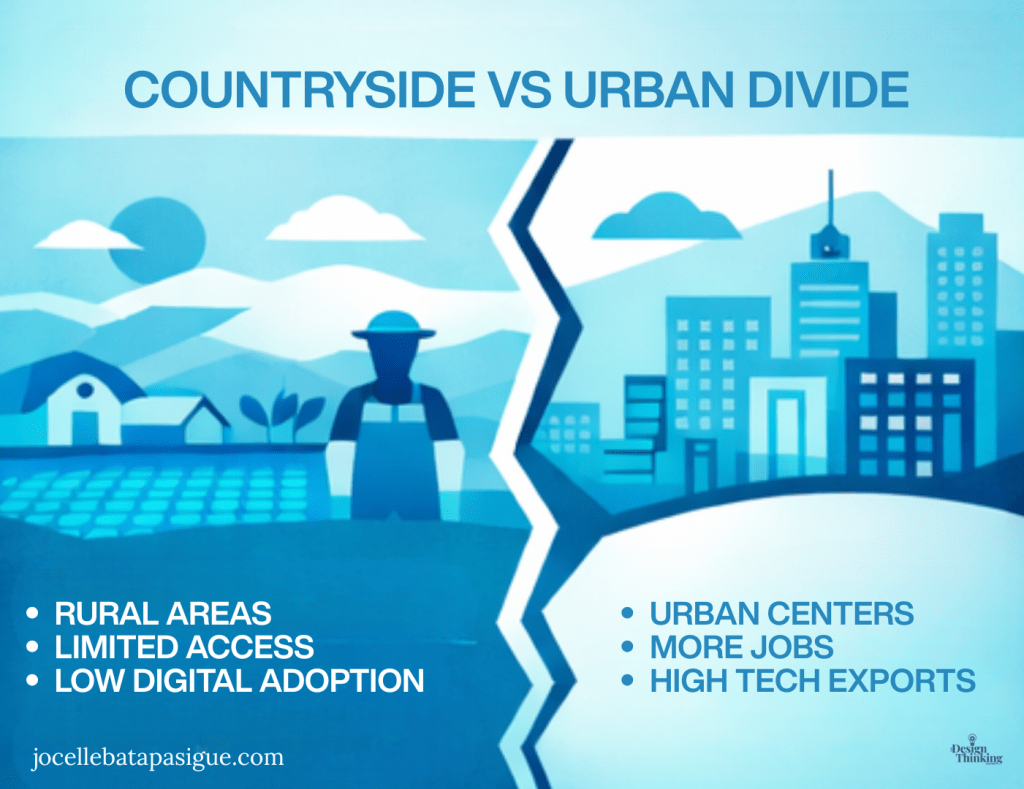

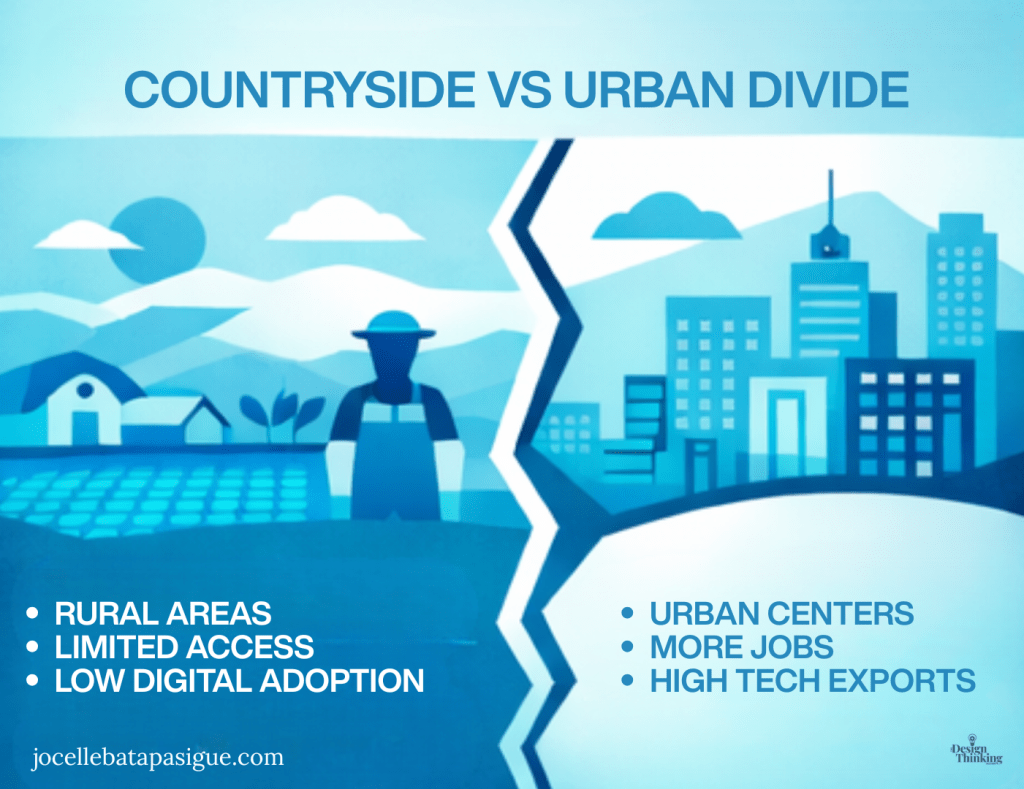

This strong showing within its income group also underscores a critical policy challenge. While the Philippines keeps pace with its peers overall, it lags in converting digital readiness into inclusive outcomes, especially in the countryside. Compared with Viet Nam’s more balanced execution and India’s scale-driven innovation, the Philippines’ main constraint lies in digital inclusion, MSME adoption, and equitable digital finance. The implication for policymakers is clear: the country’s priority is no longer catching up in connectivity, but closing internal digital gaps so that digital transformation benefits rural communities, small enterprises, and lower-income households as much as it does urban and high-skill sectors.

The most consequential of these weaknesses is digital inclusion, particularly in the countryside and among lower-income populations. The Philippines ranks 104th in the Inclusion sub-pillar, with an especially poor showing in the socioeconomic gap in digital payments (118th) and persistent rural-urban disparities. This is not a marginal concern. In the NRI framework, inclusion is not a social add-on; it is a core determinant of whether digital transformation delivers public value.

Using the NRI 2025 as its analytical foundation, this article situates the Philippines’ performance in comparative perspective with regional peers, identifies the policy levers that matter most, and proposes a reframing of digital policy—one that places countryside inclusion, MSME digitization, and equitable digital finance at the center of national digital strategy.

Regional Leaders

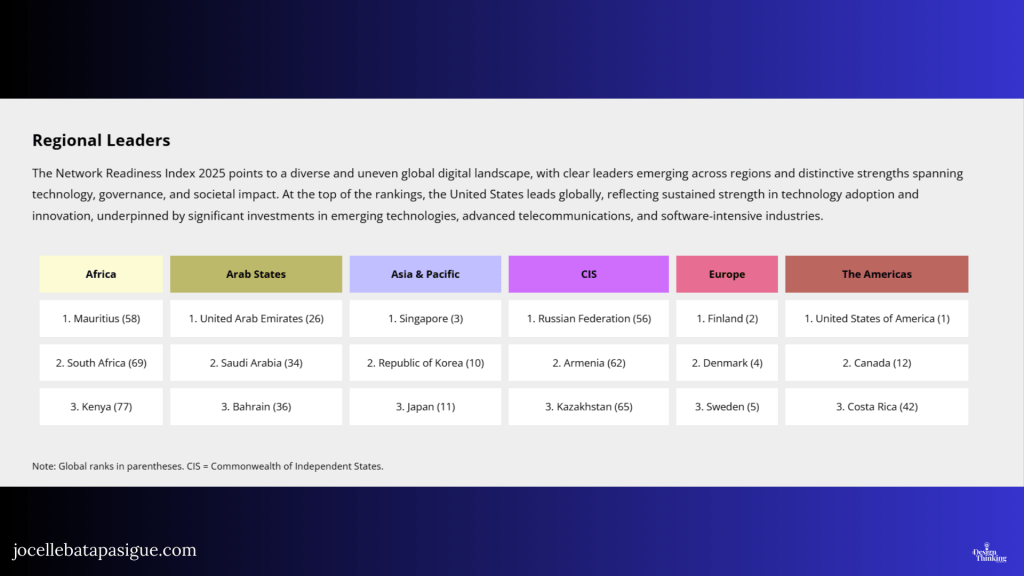

The Network Readiness Index 2025 shows that digital leadership is distributed across regions, with different economies emerging as leaders based on how well they align technology, people, governance, and impact within their regional contexts. In Africa, Mauritius leads, followed by South Africa and Kenya, reflecting comparatively stronger institutions and digital policy execution. Among the Arab States, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain stand out, driven by state-led digital transformation strategies, investment in emerging technologies, and coherent regulatory frameworks. In Asia and the Pacific, leadership is anchored by Singapore, followed by the Republic of Korea and Japan, all of which combine advanced infrastructure with high digital skills and innovation capacity.

In Europe, regional leadership is dominated by Finland, Denmark, and Sweden, highlighting the central role of strong governance, trust, and the ability to translate digitalization into social and economic outcomes. Within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Russian Federation, Armenia, and Kazakhstan lead, reflecting uneven but advancing institutional readiness. In the Americas, the United States of America leads globally, followed by Canada and Costa Rica. Taken together, these regional leaders reinforce a core NRI insight: digital readiness is shaped less by geography or income, and more by governance quality and the capacity to convert digital capability into inclusive societal impact.

Global Leaders

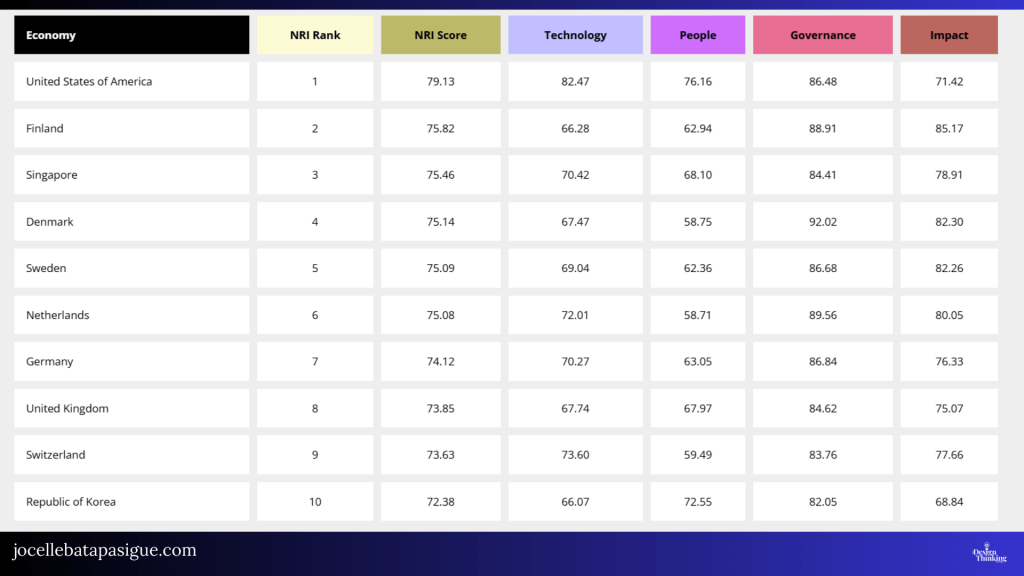

The highest-ranked economies in the Network Readiness Index 2025 include the United States of America, Finland, Singapore, Denmark, Sweden, Netherlands, Germany, United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the Republic of Korea. Despite differences in size, geography, and political systems, these economies share a consistent pattern: they perform strongly across all four NRI pillars—Technology, People, Governance, and Impact. Their digital strength is not confined to infrastructure or innovation alone, but is reinforced by capable institutions, high levels of digital skills, and policy environments that promote trust, competition, and long-term investment.

What ultimately distinguishes these countries is their ability to translate digital readiness into real societal and economic outcomes. Strong governance ensures that technology adoption leads to productivity gains, quality public services, and improved quality of life, rather than fragmented or unequal benefits. Even among these leaders, variations across the Impact pillar highlight that digital adoption by people and businesses must be matched by effective policy execution and inclusive institutions. For policymakers elsewhere, the collective experience of these ten economies reinforces a central lesson of the NRI: sustainable digital leadership depends on balance—aligning technology, skills, regulation, and inclusion to ensure that digital transformation delivers broad and lasting public value.

Importance of the Network Readiness Index for Policymakers

The Network Readiness Index is not a technology ranking. It is a governance and development diagnostic tool. Its four pillars—Technology, People, Governance, and Impact—are deliberately designed to assess not only whether digital infrastructure exists, but whether societies are capable of using digital technologies to generate economic opportunity, social inclusion, and quality of life.

For policymakers, one of the Network Readiness Index’s most important strengths is its comparability, which allows countries at similar income levels to be assessed on a level playing field. This matters greatly for countries like the Philippines, which are often measured against advanced economies with vastly different resources. By benchmarking performance against true peers, the NRI reveals whether progress—or stagnation—is the result of structural constraints or of policy choices. In this sense, comparability shifts the policy conversation away from excuses rooted in income level and toward accountability for how effectively existing resources and capabilities are used.

Equally important is the NRI’s granularity, which disaggregates digital readiness into clear pillars, sub-pillars, and indicators. This level of detail exposes where strengths are genuine and where weaknesses persist, rather than masking them behind aggregate scores. Jocelle emphasizes that this granularity is what makes the index actionable: it shows, for example, how strong individual digital engagement can coexist with weak inclusion or business adoption. These contrasts are not accidental; they point directly to areas where policy alignment has broken down, particularly in translating national digital strategies into outcomes for the countryside and underserved sectors.

Finally, the NRI’s enduring value lies in its policy relevance. Many of its indicators correspond directly to regulatory frameworks, public investment priorities, and institutional capacity—areas squarely within the control of policymakers. From my perspective, this makes the index less a diagnostic of technology and more a mirror of governance. Where performance is strong, it reflects coherent regulation and sustained public action; where it is weak, it signals gaps in coordination, execution, or inclusion. Read this way, the NRI becomes not just a measurement tool, but a guide for recalibrating digital policy toward inclusive, regionally balanced, and development-oriented outcomes.

In the 2025 edition, the Philippines is explicitly identified as a digital out-performer relative to income. This recognition is important. It confirms that constraints to digital development are not primarily fiscal or structural, but institutional and strategic.

The Philippines’ Digital Profile: Strength Without Balance

Overall Standing

The Philippines’ overall NRI rank of 66 places it in the middle of the global distribution, but near the top of its income group. This position reflects a pattern seen across several middle-income economies: strong people-level digital engagement combined with uneven institutional performance.

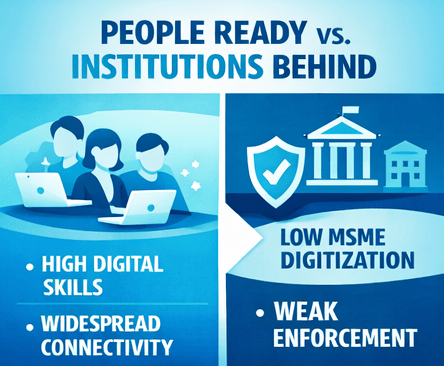

These spikes and troughs reflect a structural imbalance in policy focus, not a lack of capability. The Philippines demonstrates pronounced strengths where policy has been consistent and people-centered—such as access, connectivity, and individual digital engagement—but equally pronounced weaknesses where institutional coordination, incentives, and execution have lagged, particularly in inclusion, MSME digitalization, and governance outcomes. In my analysis, this pattern is emblematic of a development trajectory where national-level digital ambition has outpaced local and sectoral delivery, especially in the countryside. Digital policy has succeeded in enabling people to come online, but it has been less effective in ensuring that being online translates into livelihood opportunity, financial inclusion, and regional economic participation.

Crucially, these troughs are most visible in areas that matter directly to inclusive growth: digital payments adoption among lower-income groups, rural participation in the digital economy, and the ability of small enterprises outside urban centers to use technology productively. This signals a need for policy realignment rather than policy expansion. From this perspective, the task ahead is not to add more digital programs, but to re-anchor digital strategy around countryside realities—where infrastructure must be paired with trust, skills with market access, and technology with governance that works at the local level. The radar chart, taken seriously, is therefore a call for corrective action: to move from fragmented digital gains toward a coherent, inclusion-driven digital development agenda that closes gaps instead of widening them.

Where the Philippines Performs Well: The Human Digital Advantage

People Pillar: Individuals as a Core Strength

The Philippines’ strongest performance is in the Individuals sub-pillar, where it ranks 5th globally. This is an extraordinary result for a lower-middle-income economy and carries important implications.

These indicators together explain why the Philippines performs strongly on the “People” dimension of the Network Readiness Index, and why its digital challenge is no longer about access but about outcomes.

First, universal mobile network coverage, with 100% of the population covered by at least a 3G network, means that basic digital connectivity has effectively reached the entire country, including rural and geographically dispersed areas. This is a critical foundation for inclusion: it ensures that distance and archipelagic geography are no longer absolute barriers to participation in the digital economy. Similarly, full Internet access in schools—ranked first globally— signals a long-term investment in digital exposure for the next generation. This is a powerful equalizer in principle, as it embeds digital familiarity early in life, regardless of location or income.

These access strengths are reinforced by a very high adult literacy rate, which allows digital tools to be adopted quickly and intuitively. High literacy lowers the friction of technology use and helps explain the Philippines’ strong engagement in mobile broadband and social networks, where Filipinos are among the most active users globally. This level of engagement reflects not only connectivity, but also cultural adaptability and social readiness for digital interaction. Importantly, it shows that people are not passive recipients of technology; they are active users who integrate digital tools into daily life, work, and communication.

Perhaps most striking is the Philippines’ relatively high AI talent concentration despite its income level. This indicates that the country is producing or attracting advanced digital skills faster than expected for its stage of development, driven by education, global work exposure, and participation in international digital services markets. In my analysis, this combination of universal access, strong literacy, deep engagement, and emerging advanced skills confirms a central point: the Philippines does not suffer from a people problem in digital transformation. The real challenge lies in converting this human digital readiness into inclusive economic opportunity—particularly for small enterprises, rural communities, and lower-income households—through better-aligned policies, institutions, and incentives.

From a policy perspective, this means that digital readiness among citizens is not the binding constraint. Filipinos are connected, digitally literate, and actively engaged. The countryside is not digitally disengaged by default. The problem lies elsewhere.

The Central Weakness: Inclusion and the Countryside Divide

Inclusion Sub-Pillar: The Philippines’ Lowest Point

The Philippines ranks 104th in the Inclusion sub-pillar, making it the weakest dimension of its digital readiness profile.

The most alarming indicator is the socioeconomic gap in the use of digital payments, where the country ranks 118th out of 127 economies. Rural gaps in digital payments are also pronounced, and while gender gaps in Internet use are narrower, they do not compensate for the broader pattern of exclusion.

This result is particularly striking given the country’s high level of mobile connectivity and social media use. It indicates that digital tools are present but not equally usable as instruments of economic participation.

Why This Matters for Countryside Development

Digital inclusion in the countryside is not merely about fairness. It is about economic structure. Rural economies in the Philippines are dominated by:

- Micro and small enterprises

- Informal employment

- Agriculture, fisheries, tourism, and local services

- Remittance-dependent households

In such contexts, digital payments, digital identity, and platform access are not conveniences; they are gateways to markets, credit, government services, and resilience against shocks. When digital finance fails to reach these populations equitably, digital transformation reinforces existing spatial inequalities instead of reducing them.

Business Digitalization: The Missing Middle

Businesses Sub-Pillar: Lagging Firm Adoption

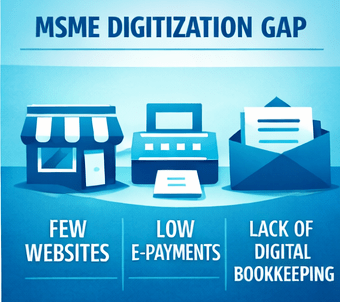

The Philippines performs poorly in the Businesses sub-pillar, ranking 76th. Indicators reveal:

- A relatively low proportion of firms with websites

- Weak venture capital activity in AI

- Limited diffusion of advanced digital tools among MSMEs

This gap explains much of the disconnect between high individual digital engagement and modest economic impact.

This set of indicators explains why the Philippines’ strong people-level digital readiness does not yet translate into firm-level productivity and inclusive economic growth. Ranking 76th in the Businesses sub-pillar reflects a structural gap between how Filipinos use digital technologies as individuals and how enterprises—especially small and micro firms—use them as tools for production, expansion, and competitiveness. A low proportion of firms with websites signals that many businesses remain digitally informal: they rely on social media or offline channels rather than establishing a stable digital presence that enables e-commerce, formal transactions, discoverability, and access to broader markets. While social platforms provide entry points, they rarely substitute for the efficiency, credibility, and scalability that formal digital business tools offer.

The weak level of venture capital activity in AI further points to limited depth in the innovation ecosystem. This does not mean that talent is absent—on the contrary, the Philippines shows relatively strong AI skills for its income level—but rather that capital, risk appetite, and institutional support for scaling advanced technologies remain constrained. As a result, AI development is often concentrated in service-oriented or outsourced functions, rather than in locally rooted, high-growth firms that could drive domestic productivity and regional development. This reinforces a pattern where advanced digital capabilities exist but are not fully anchored in the local business ecosystem.

Finally, the limited diffusion of advanced digital tools among MSMEs is particularly consequential for countryside development. MSMEs dominate the Philippine economy and are the backbone of rural livelihoods, yet many lack access to affordable digital finance, cloud services, data analytics, or AI-enabled tools that could improve efficiency and resilience. From my analysis, this is not primarily a skills problem but an incentives and delivery problem: policies have focused more on connectivity and training than on sustained adoption and use. Without deliberate support to integrate digital tools into everyday business operations—especially outside urban centers—digital transformation risks deepening the gap between digitally ready people and digitally underpowered enterprises, limiting its impact on inclusive growth.

MSMEs and the Countryside

In the countryside, MSMEs are not just economic actors; they are social infrastructure. When they fail to digitize, entire communities are excluded from:

- E-commerce value chains

- Digital procurement

- Formal finance

- Productivity-enhancing technologies

The NRI data suggest that Philippine digital policy has been people-centric but firm-agnostic. This imbalance is costly.

Governance: Adequate Rules, Uneven Outcomes

Regulation and Trust

The Philippines’ governance performance is mixed. It performs reasonably in certain regulatory indicators, including e-commerce legislation, but less well in trust-related dimensions such as privacy protection and cybersecurity confidence.

For policymakers, the key insight is that formal rules exist, but enforcement, coordination, and local capacity vary widely, particularly outside metropolitan areas.

This assessment means that the Philippines has put in place many of the formal legal and policy foundations for the digital economy, but has not yet achieved consistent, system-wide effectiveness in how these rules are applied and experienced by users. Reasonable performance in areas such as e-commerce legislation indicates that the country recognizes the importance of enabling online transactions, digital trade, and platform-based business. These frameworks provide legal certainty for digital activity and signal policy intent to support the digital economy. However, strong laws on paper do not automatically translate into trust in practice.

The weaker performance in trust-related dimensions—particularly privacy protection and cybersecurity confidence— points to gaps in enforcement, institutional coordination, and public assurance. From my analysis, this is especially evident outside major metropolitan areas, where local government units and smaller institutions often lack the technical capacity, resources, or clarity of mandate to implement national digital policies effectively. As a result, citizens and small businesses may be connected and digitally active, yet remain hesitant to fully engage in digital payments, data sharing, or online services due to concerns about security, misuse of data, or inadequate recourse when problems arise.

For policymakers, the central insight is that digital governance is no longer a legislative challenge but an execution challenge. The Philippines does not need more rules as much as it needs stronger coordination across agencies, clearer accountability, and capacity-building at the local level—particularly in the countryside. Without this, digital transformation risks remaining uneven: advanced in urban centers with stronger institutions, but fragile in rural areas where trust, enforcement, and support systems are weakest. Strengthening governance, therefore, is not only about compliance; it is a prerequisite for inclusive digital participation and sustained public confidence in the digital ecosystem.

Impact: Economic Strengths, Social Limits

Economic Impact

The Philippines performs relatively well in aspects of the digital economy, including ICT services exports and technology-enabled work flexibility. These results reflect the strength of the BPO sector and the country’s role in global digital services.

However, these benefits are geographically concentrated. They accrue primarily to urban centers and skilled workers, reinforcing the countryside-city divide.

This means that the Philippines has been successful in leveraging digital technologies for certain economic activities, particularly in areas where it has developed global competitiveness. Strong performance in ICT services exports and technology-enabled work flexibility reflects the maturity of the business process outsourcing (BPO) and global services sector, as well as the country’s ability to integrate into international digital value chains. These sectors benefit from a digitally skilled workforce, widespread connectivity, and familiarity with remote and platform-based work, allowing the Philippines to generate jobs, foreign exchange, and economic growth through digital services.

However, these gains are not evenly distributed across the country. They are largely concentrated in urban centers, where digital infrastructure, corporate offices, higher education institutions, and skilled labor are clustered. As a result, urban, college-educated workers benefit disproportionately, while many rural communities and lower-skilled workers remain on the margins of the digital economy. From Jocelle’s analysis, this concentration reinforces the countryside–city divide: digital transformation creates visible success stories, but without deliberate policies to extend digital work, services, and enterprise opportunities to rural areas, it risks deepening regional inequality rather than reducing it.

Quality of Life and SDGs

Performance in SDG contribution, especially in education quality and health outcomes, remains weak. This suggests that digital transformation has not yet been systematically harnessed to improve basic human development outcomes, particularly in underserved regions.

Comparative Perspective: Lessons from Regional Peers

Compared with Viet Nam, India, and Indonesia—countries that also outperform their income level—the Philippines stands out for strong people readiness but weaker inclusion outcomes.

- Viet Nam shows more balanced execution across pillars

- India excels in scale and AI investment, though inclusion challenges persist

- Indonesia has leveraged state-led digital platforms to broaden digital payments adoption

The Philippines’ relative underperformance in inclusion is therefore not inevitable. It reflects policy choices

This comparison highlights a distinctive structural pattern in the Philippines’ digital development when viewed alongside Viet Nam, India, and Indonesia—all of which, like the Philippines, outperform what their income level would normally predict in the Network Readiness Index. The Philippines matches or exceeds these peers in people readiness: it has near-universal mobile connectivity, high digital engagement, strong literacy, and a relatively deep pool of digital and AI-capable talent. In practical terms, Filipinos are well prepared to use digital tools, adopt new technologies, and participate in online work and services. This places the country on solid footing for digital transformation from a human-capability standpoint.

However, the divergence becomes clear when looking at inclusion outcomes. Compared with Viet Nam’s more even integration of digitalization into manufacturing and regional economies, India’s large-scale digital public infrastructure that broadens access to payments and services, and Indonesia’s state-led push to expand digital payments and platforms nationwide, the Philippines shows weaker translation of digital readiness into inclusive participation. Digital finance, MSME adoption, and rural integration lag behind people-level readiness, meaning that access and skills do not consistently result in economic opportunity for lower-income households and countryside communities. From Jocelle’s analysis, this gap reflects not a failure of ambition or talent, but a misalignment between national digital strategies and local delivery mechanisms. The implication for policymakers is clear: the Philippines’ next phase of digital policy must focus less on expanding access—which it has largely achieved—and more on closing internal inclusion gaps, so that digital transformation delivers benefits across regions, sectors, and income groups rather than reinforcing existing divides.

Policy Implications: Reframing Digital Strategy Around Inclusion

From Access to Participation

The NRI 2025 makes clear that the Philippines has crossed the access threshold. The next phase of digital policy must focus on participation—who benefits, where, and how.

Countryside-First Digital Policy

A countryside-first approach does not mean slowing innovation. It means:

- Designing digital finance systems that work for low-income and rural users

- Making MSME digitization a condition—not an option—for public support

- Using AI and data to improve rural service delivery

- Treating digital inclusion as economic infrastructure, not social assistance

These four policy directions together describe a shift from access-oriented digital policy to inclusion-driven economic policy, particularly relevant for countryside development.

First, designing digital finance systems that work for low-income and rural users means building financial tools around the realities of informal incomes, limited documentation, intermittent connectivity, and low transaction values. In practice, this requires simple onboarding, low or zero fees, offline-capable transactions, local agent networks, and strong consumer protection. The goal is not just to make digital payments available, but to make them useful, trusted, and affordable for farmers, micro-entrepreneurs, and rural households—so that digital finance becomes a gateway to savings, credit, insurance, and market access, rather than a barrier.

Second, making MSME digitization a condition—not an option—for public support reframes digital adoption as a core business requirement rather than a voluntary upgrade. This means linking access to government loans, subsidies, procurement, and training programs to concrete digital practices such as e-payments, basic online presence, digital bookkeeping, or platform participation. Jocelle emphasizes that this approach moves policy beyond awareness-raising toward behavioral change at scale, ensuring that public resources actively accelerate MSME productivity and integration into the digital economy, especially in rural areas.

Third, using AI and data to improve rural service delivery focuses on applying technology where it can have the highest public value. AI can help identify service gaps, target social and agricultural support more accurately, optimize health and education delivery, and anticipate risks such as crop failure or disease outbreaks. The emphasis here is not on advanced or experimental AI, but on practical, ethical, and context-aware applications that strengthen local government capacity and improve outcomes for underserved communities.

Finally, treating digital inclusion as economic infrastructure rather than social assistance represents a fundamental policy shift. Just as roads, electricity, and irrigation are investments that enable productivity, digital inclusion—through connectivity, finance, skills, and trust—should be understood as a foundational input to economic growth and regional development. From Jocelle’s perspective, this framing is critical: it positions digital inclusion not as a temporary subsidy for the poor, but as a long-term investment in national competitiveness, countryside resilience, and shared prosperity.

Inclusion as the Measure of Digital Success

The Network Readiness Index 2025 sends a clear message to Philippine policymakers: digital readiness without inclusion is fragile. The country’s people are ready. Its technology is present. Its institutions must now close the gap.

If the Philippines succeeds in embedding digital inclusion—especially in the countryside—into its core digital strategy, it will not only improve its NRI ranking. More importantly, it will ensure that digital transformation becomes a tool for national cohesion, regional development, and shared prosperity. That is the real measure of network readiness.

Below is a revised, policy-forward version of the strategy that removes personal references, sharpens the policy substance, and clearly highlights what policies are needed, written in a tone appropriate for national leaders, legislators, senior regulators, and development partners.

From Digital Potential to Shared Prosperity: A Strategic Digital Inclusion and Countryside Development Agenda for the Philippines

Strategic Diagnosis: The Gap Is Policy Execution, Not Technology

Recent assessments of the Philippines’ digital readiness show a country that has already achieved widespread connectivity, high individual digital engagement, and strong human capital fundamentals. These are not trivial accomplishments, particularly for a lower-middle-income economy. However, they coexist with persistent weaknesses in digital inclusion, MSME digital adoption, trust, and regional equity, especially outside major urban centers.

The central challenge is therefore not accelerating digitalization per se, but realigning policy, institutions, and incentives so that digital transformation produces inclusive economic outcomes. Digital tools are available; what is missing is a coherent policy framework that ensures these tools are systematically used to expand opportunity in the countryside, strengthen small enterprises, and reduce spatial inequality.

This requires a shift in mindset: digital inclusion must be treated as a core economic and regional development policy, not as a secondary social or ICT concern.

Strategic Direction: Fewer Initiatives, Stronger Policy Anchors

Given institutional constraints and uneven local capacity, the Philippines cannot pursue a fragmented or overly ambitious digital agenda. What is required is policy discipline—focusing on a limited number of high-impact reforms that are feasible within existing governance structures and capable of scaling nationally. Four policy anchors emerge as priorities.

Priority Policy Areas

1. Institutionalize Digital Inclusion as Economic Infrastructure

Adopt a national policy framework that formally recognizes digital inclusion—connectivity, digital finance, basic digital tools, and trust—as economic infrastructure, equivalent in importance to roads, ports, and power.

Key Actions:

- Integrate digital inclusion targets into regional and local development plans, not only national ICT strategies.

- Require national agencies to align digital programs with regional economic priorities (agriculture, tourism, MSMEs, logistics).

- Establish outcome-based metrics that track usage, participation, and geographic distribution, not just access.

Without this shift, digital initiatives will continue to benefit areas that are already economically advantaged, reinforcing the countryside–city divide.

2. Make MSME Digitization a Policy Default, Not a Choice

MSME participation in public programs to minimum digital operating standards.

Key Actions:

- Condition access to government credit, guarantees, subsidies, and procurement on the use of:

- digital payments

- basic digital records

- simple online presence or platform participation

- Provide shared digital services (payments, accounting, compliance tools) to reduce cost and complexity for small firms.

- Prioritize MSMEs in rural areas and secondary cities in program design and rollout.

MSMEs dominate the Philippine economy and countryside employment. Without their digitization, digital growth will remain narrow and urban-centered.

3. Redesign Digital Finance for Low-Income and Rural Use

Shift digital finance policy from platform expansion to effective, trusted use by low-income and rural populations.

Key Actions:

- Mandate interoperability and low transaction costs for small-value payments.

- Strengthen consumer protection, dispute resolution, and data privacy enforcement.

- Support local intermediaries (cooperatives, rural banks, associations) as trusted access points.

- Align government transfers, fees, and procurement with digital payment systems that work in rural contexts.

Digital finance that excludes informal and rural users undermines inclusion and limits economic participation.

Use AI and Data to Strengthen Local Public Service Delivery

Position AI and data analytics as tools for improving public-sector capacity, not just private innovation.

Key Actions:

- Deploy AI for practical applications in health, education, agriculture, disaster response, and social protection.

- Invest in local government data capability, including shared platforms and technical support.

- Adopt clear standards for ethical, transparent, and accountable AI use, especially where citizens’ data are involved.

AI can help compensate for capacity gaps in underserved areas, but only if deployed responsibly and purposefully.

Governance and Leadership Requirements

Policy reform alone is insufficient without the right kind of leadership and institutional behavior.

The Philippines now needs leaders who:

- Prioritize execution over announcements, focusing on coordination, enforcement, and follow-through

- Understand countryside realities, including informality, local capacity limits, and trust dynamics

- Value inclusion and trust as strategic assets, not compliance burdens

- Work across institutional boundaries, recognizing that digital transformation cuts across sectors and levels of government

- Accept iterative reform, piloting, learning, and adjusting rather than waiting for perfect conditions

Digital transformation at this stage is a governance and leadership challenge, not a technological one.

Strategic Bottom Line

The Philippines has reached a turning point in its digital development. It has already built the foundations of connectivity and skills. The defining question now is whether public policy can convert digital readiness into shared prosperity, particularly for the countryside and small enterprises that anchor the national economy.

A strategy centered on digital inclusion as economic infrastructure, MSME digitization by default, rural-ready digital finance, and practical use of AI in public services offers a realistic and high-impact path forward. Success will depend not on adopting more technologies, but on aligning policy, institutions, and leadership around inclusion as the core measure of digital progress.

PHILIPPINES DIGITAL READINESS SCORECARD (2022–2025)

Network Readiness Index (NRI) by Portulans Institute

Overall Trajectory

Direction: Gradual improvement

Position: Consistently outperforming income peers, but with persistent structural gaps

Insight: Progress since 2022 has been real but uneven—strongest where individuals act, weakest where institutions and incentives matter.

PILLAR 1: TECHNOLOGY

Trend since 2022: Slight improvement

Current State: Strong access, limited depth

What improved

- Near-universal mobile network coverage sustained

- Connectivity and affordability indicators stabilized

- School internet access strengthened

What did not

- Limited progress in future technologies (AI, R&D, advanced infrastructure)

- Shallow domestic technology production and scale-up

Policy Meaning: The Philippines has secured the digital foundation, but has not moved decisively into technology depth or innovation-led growth.

PILLAR 2: PEOPLE

Trend since 2022: Strong, sustained improvement

Current State: Major national strength

What improved

- High and growing individual digital engagement

- Very strong literacy and education access

- Rising visibility of digital and AI-capable talent

Structural issue

- Skills concentrated at the individual level, not consistently embedded in firms or rural livelihoods

Policy Meaning: The country is people-ready for the digital economy. This is the main driver of rank improvement since 2022.

PILLAR 3: GOVERNANCE

Trend since 2022: ➖ Largely flat

Current State: Rules exist, execution uneven

What held steady

- E-commerce and digital economy legislation

- Formal regulatory frameworks

What remains weak

- Trust indicators (privacy, cybersecurity confidence)

- Uneven enforcement and coordination

- Large gaps in local government capacity

Policy Meaning: The constraint is not policy intent but policy execution, especially outside major urban centers.

CROSS-CUTTING: INCLUSION

Trend since 2022: ➖ Persistent weakness

Current State: Lowest-performing dimension

Ongoing issues

- Large socioeconomic gap in digital payments

- Rural-urban participation divide

- Digital tools under-serve informal and low-income users

Policy Meaning: Inclusion has not improved at the same pace as access or skills. This is the single most binding constraint on inclusive digital growth.

PILLAR 4: IMPACT

Trend since 2022: Selective gains

Current State: Economic impact without broad spillovers

Where performance is strong

- ICT services exports

- Technology-enabled work flexibility

Where impact is limited

- Quality-of-life outcomes

- Education and health SDG indicators

- Geographic concentration of benefits

Policy Meaning: Digitalization is generating value—but not evenly, reinforcing the countryside–city divide.

BUSINESSES (KEY SUB-PILLAR)

Trend since 2022: Weak and largely unchanged

Current State: Persistent lag

Structural issues

- Low share of firms with websites or digital records

- Weak AI and innovation investment

- Limited MSME adoption of advanced tools

Policy Meaning:

MSME digitization is the missing middle between people readiness and inclusive economic impact.

SINCE 2022: WHAT CHANGED VS WHAT DID NOT

Improved

- Individual digital readiness

- Connectivity and access

- Some digital economic outputs

Did not improve materially

- Inclusion outcomes

- MSME digital adoption

- Local governance capacity

- Distribution of digital benefits

BOTTOM-LINE SCORECARD MESSAGE

Since 2022, the Philippines has progressed—but asymmetrically.

The country advances fastest where individual capability drives outcomes, and slowest where institutions, incentives, and local capacity are decisive.

Strategic Implication: Future gains will not come from more connectivity or skills alone, but from policies that convert readiness into inclusion, especially in the countryside.

Portulans Network Readiness Index (NRI)

The Portulans Network Readiness Index (NRI) is a global benchmarking framework developed by the Portulans Institute to assess how well countries are positioned to harness digital technologies for inclusive and sustainable development. First introduced in 2002 and continuously refined, the NRI goes beyond measuring connectivity or technology adoption alone. Its core purpose is to evaluate whether digital transformation is being translated into economic opportunity, effective governance, and improved quality of life, recognizing that technology is only meaningful insofar as it delivers public value.

The NRI 2025 evaluates 127 economies using a structured framework built around four pillars: Technology, People, Governance, and Impact. These pillars are further broken down into 12 sub-pillars and 53 indicators, drawing on internationally comparable data from sources such as the World Bank, ITU, UNESCO, and other reputable institutions. The methodology deliberately balances “hard” infrastructure indicators (such as broadband coverage) with “soft” institutional and societal indicators (such as digital skills, trust, inclusion, and regulatory quality). Scores are normalized on a 0–100 scale, allowing for consistent comparison across countries and income groups.

What distinguishes the Portulans NRI from many other digital indices is its explicit focus on outcomes and inclusion, not just inputs. The index emphasizes that digital readiness is shaped as much by policy choices, governance quality, and institutional execution as by income level or technological capacity. As a result, the NRI highlights why some middle- and lower-income countries outperform expectations, while some high-income economies underperform. For policymakers, the NRI serves as a diagnostic and strategic tool: it helps identify where digital progress is strong, where it is uneven, and where targeted reforms—particularly in areas such as inclusion, MSME digitalization, education, and governance—are necessary to ensure that digital transformation benefits the whole of society, including rural and underserved communities.

Leave a comment