Building an Age-Inclusive Digital Future for the Philippines: Key Takeaways from the UNESCAP Workshop on Digital Literacy for Older Persons (18–20 November 2025)

Introduction: A New Demographic Chapter for the Philippines

The latest ESCAP population charts for the Philippines tell a compelling story — one of transformation, urgency, and opportunity. In just a few decades, the country is moving from a classic “young” nation to a maturing and eventually ageing society. This demographic shift will profoundly affect how Filipinos live, work, and connect.

For policymakers, educators, entrepreneurs, and digital advocates, this shift presents both a narrow window for a demographic dividend and a rapidly approaching transition to a silver economy. The challenge is clear: to build systems — in education, health, pensions, and digital inclusion — that can adapt to a society growing older, even as it strives to stay competitive and connected in the digital age.

1. From a Young Nation to a Maturing Society

A Generation in Transition

The Philippines is undergoing a rapid demographic transition. UN ESCAP’s population pyramids for 1990, 2020, 2030, and 2050 show a clear movement from a youthful society to a more mature—and eventually ageing—population. This shift will transform the country’s development landscape, with consequences for the labour market, social protection systems, digital inclusion strategies, and national innovation capacity.

Understanding the Demographic Shift

UN ESCAP’s selected-year population pyramids illustrate the following:

1990: A Young, High-Fertility Population

- Wide base with children aged 0–14 comprising the largest segment.

- Seniors (60+) represent a very small share.

- High youth dependency creates pressure on education and basic services.

2020: Transition Toward a Mature Structure

- Fertility decline begins to reshape the population.

- Largest cohorts now aged 20–34—workers, not children.

- Early signs of ageing appear, though still limited.

2030: Peak Demographic Dividend Window

- Working-age groups (20–54) dominate the population.

- Youth share declines; senior population grows but remains manageable.

- This is the period with the highest productivity potential.

2050: Rapid Ageing Emerges

- Smaller base and rounded upper structure indicate low fertility and increased longevity.

- Older Filipinos become a major demographic bloc.

- Social protection, healthcare, and labour policies face higher demand.

The Philippines is moving through a major demographic shift. In 1990, the country had a very youthful population — children made up almost 40% of all Filipinos, creating the wide base of the classic “young nation” pyramid. Over the years, this share has steadily declined. By 2024, children under 15 account for less than 28% of the population, and by 2050 they are expected to make up only about 1 in 5 Filipinos. This steady narrowing of the pyramid’s base shows how fertility has dropped and families have become smaller.

At the same time, the working-age population has grown and now dominates the country’s age structure. Today, about two-thirds of Filipinos are between 15 and 64 years old — the highest share in our history — and this will remain strong through 2050. This “middle bulge” is the demographic dividend: a period when the country has more workers than dependents, creating a unique window for economic growth if jobs and skills are available.

But as the youth share shrinks and the large working-age cohort begins to age, the number of older Filipinos is rising quickly. What was once a very small group — with only a thin line at the top of the 1990 pyramid — is expanding sharply. Seniors aged 65 and above made up just 5.5% of the population in 2024; by 2050, they are projected to double to more than 11%. In real numbers, older Filipinos will grow from roughly 9 million in 2020 to nearly 24 million by mid-century. The 2050 pyramid clearly shows this shift: a much wider top, signaling a transition into an ageing society.

This transformation is both a demographic success and a policy challenge. Fewer children ease pressure on schools and youth services, but more elderly Filipinos will soon require healthcare, social protection, and community support.

Social protection, healthcare, and labor policies face higher demand. The coming decade (2025–2035) represents the critical window for maximizing the demographic dividend. After 2035, the population will age more quickly, requiring new approaches in digital governance, healthcare, workforce upskilling, and age-inclusive socioeconomic planning. Strategic investment in ICT infrastructure, regional innovation hubs, and AI-ready human capital will determine whether the Philippines sustains productivity or faces structural slowdown.

2. The Median Age: A Mirror of Modernization

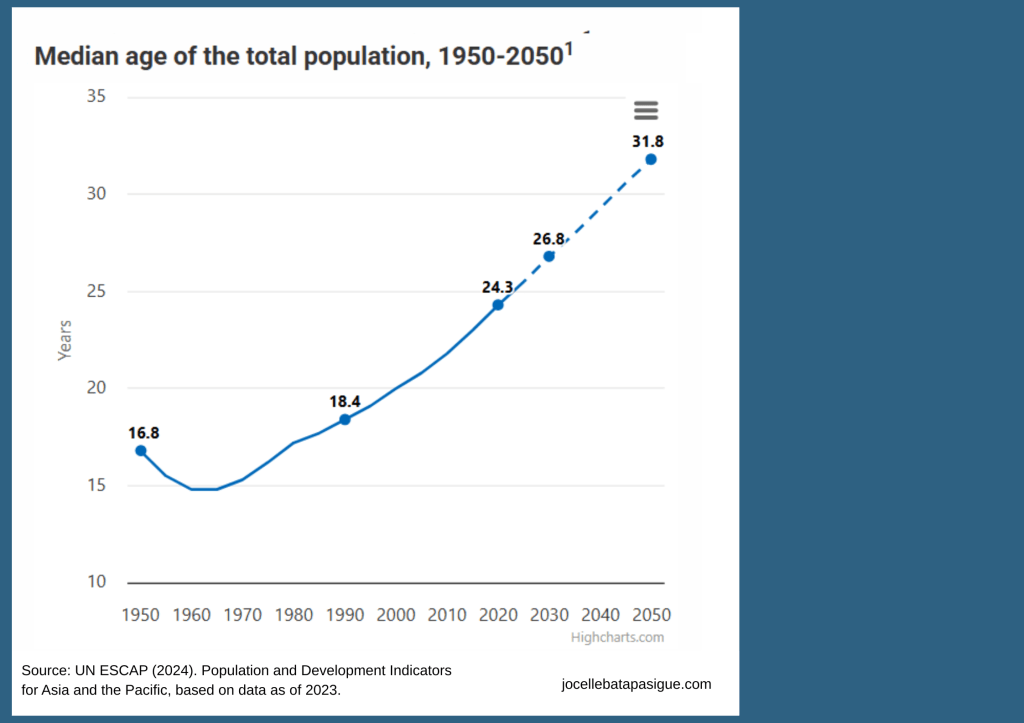

The steady rise in the median age of Filipinos—from 16.8 years in 1950 to 24.3 years in 2020, and projected to reach 31.8 years by 2050—marks one of the most defining social transformations in the country’s modern history. This trend mirrors the broader demographic shift across Asia and the Pacific, where countries are transitioning from “young and growing” to “maturing and aging” populations.

The median age of Filipinos has been rising steadily for decades, showing how the country is shifting from a very young population to a more mature and eventually ageing society. In 1950, the median age was just 16.8 years, reflecting high fertility and a large number of children. It dipped slightly in the 1960s due to a post-war baby boom, but from the 1970s onward the trend reversed as families became smaller and people lived longer.

By 1990, the median age climbed to 18.4 years, and by 2020 it had increased sharply to 24.3 years. Projections show this rise continuing: about 26.8 years by 2030, and 31.8 years by 2050. This means that within one generation, the typical Filipino will be more than ten years older than today. In simple terms: the Philippines is ageing, driven by fewer births and longer life expectancies.

The shift brings both opportunities and challenges — from a stronger workforce today to a much larger senior population in the decades ahead.

This statistics is a reflection of modernization: smaller families, longer lives, better health, and higher aspirations. However, it also signals that systems built for a young population will soon be outdated.

The Philippines will still be younger than Japan or Korea by mid-century, but it will no longer be a youthful society. National planning, urban design, and social policy must evolve to support adults and seniors as much as children and youth.

3. Longer Lives, Different Challenges

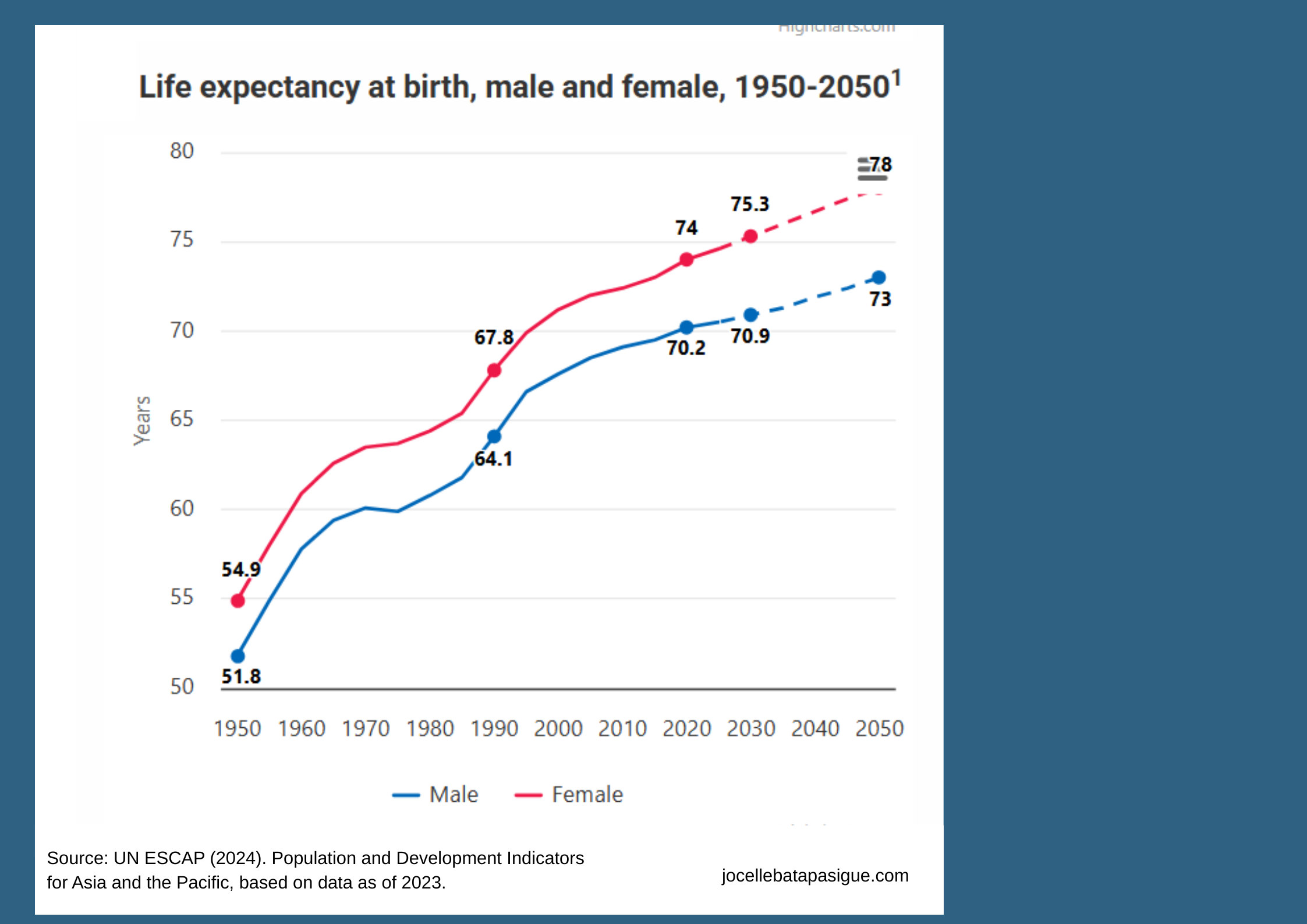

Between 1950 and 2050, Filipino life expectancy rises by over 20 years — from roughly 52 for men and 55 for women in 1950, to about 73 and 78 respectively by 2050.

While this is a triumph of development — a testament to public health, nutrition, and healthcare improvements — it also transforms social and economic realities.

Older Filipinos will increasingly live with chronic diseases rather than infectious ones. They will require long-term, community-based care systems — and, equally important, digital health solutions to bridge access gaps between rural and urban areas.

The feminization of ageing also deserves urgent attention: women live longer but often with less income security, having spent more years in unpaid care work. This demands gender-responsive social protection systems.

4. The Speed of Ageing: Less Time to Prepare

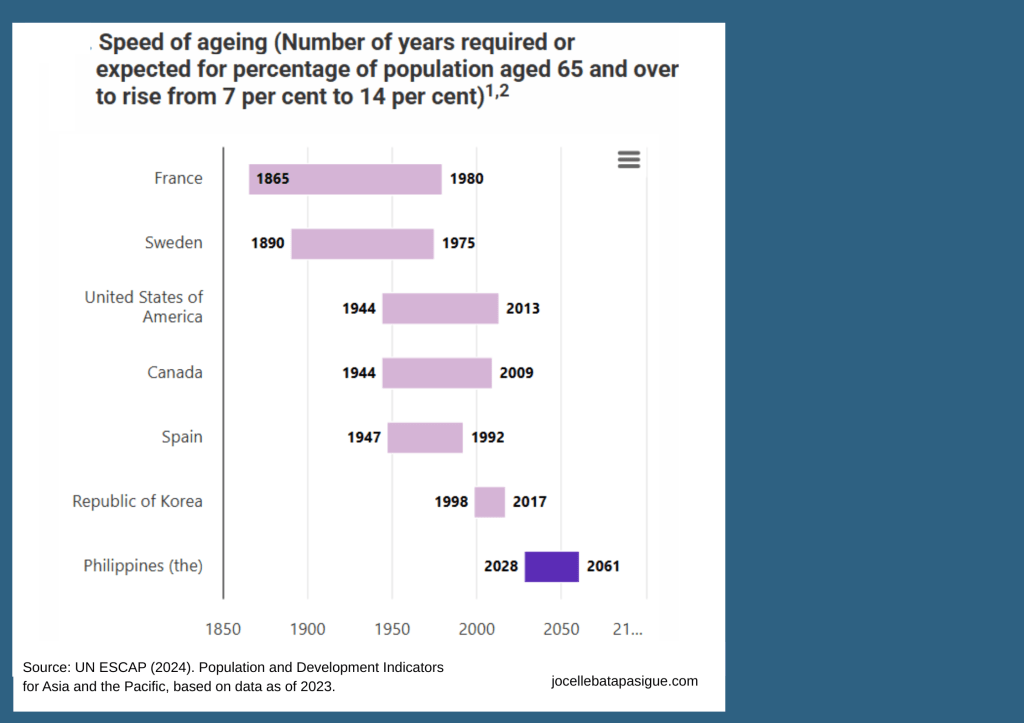

In Europe, the transition from 7% to 14% of the population aged 65+ took more than a century. For the Philippines, it will take just 33 years (2028–2061).

This accelerated ageing gives the country far less time to prepare — especially since social protection coverage remains limited and health systems are unevenly distributed.

The lesson from East Asia is clear: ageing starts slowly and ends suddenly. Policies must get ahead of the curve — not react to it.

The window for preparation is the next 10–15 years — the same period in which the country can still reap the benefits of its demographic dividend.

5. The Demographic Dividend Window: A Decade of Decision

With over 64% of Filipinos now in their working ages (15–64), the country sits at a golden intersection: fewer dependents and more potential producers.

But a dividend is not automatic. It requires that workers be healthy, skilled, and productively employed. Without inclusive job creation and re-skilling, the dividend could become a demographic burden, with millions of underemployed youth or discouraged workers.

Demographic Dividend: A Window of Opportunity

The Philippines still enjoys a relatively youthful workforce, with over 60% of the population below 35 years old. This provides a short-term demographic dividend—a potential boost to productivity and economic growth if the population is equipped with digital and future-ready skills.

However, ITU and WEF reports emphasize that the window for this dividend is closing rapidly. Unless the workforce transitions into high-value, digital-intensive jobs, the country could miss this opportunity and face rising dependency ratios by 2050.

6. Policy Pathways for an Ageing-Ready and Digitally Inclusive Philippines

6.1 Education and Skills

According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2025, digital access, AI, and automation are the top drivers transforming global work. The same report identifies “technological literacy” and “resilience” as the fastest-growing skills.

The Philippines must therefore move beyond enrollment targets and towards skills transformation — focusing on quality, adaptability, and inclusion.

Programs inspired by the AI for All Initiative (2025) recommend “AI readiness across all sectors” and “reskilling through inclusive digital learning pathways,” particularly targeting women and rural communities.

6.2 Productive and Inclusive Employment

The WEF Rise of Global Digital Jobs (2024) white paper found that remote and digital jobs could help emerging economies like the Philippines bridge the urban-rural divide.

Coupled with investments in broadband and digital infrastructure — emphasized by the ITU State of Digital Development in Asia and the Pacific (2025) — this creates new opportunities for countryside innovation and inclusive digital work.

Meanwhile, AI adoption (as highlighted in Harnessing AI: Transforming Southeast Asia’s Workforce) could add US$1 trillion to regional GDP by 2030, but only if countries build an AI-ready workforce.

6.3 Health Systems and Long-Term Care

With life expectancy rising and chronic diseases increasing, healthcare must shift from hospital-centered to community-based. The McKinsey Health Institute’s “Age is Just a Number” study (2023) found that older adults value purpose, connection, and independence as much as clinical care.

Digital health platforms, telemedicine, and home-based care — integrated with human-centered design — can help deliver those outcomes affordably and inclusively.

6.4 Social Protection and Pension Reform

Social pensions must evolve from youth-centered to life-course systems, ensuring security from early adulthood through old age. Expanding universal pension coverage, particularly for informal workers and women, is key to resilience in an ageing economy.

The ITU’s Digital Economy and Fiscal Reports (2025) note that effective digital service taxation and inclusion policies can help governments expand fiscal space for such reforms.

6.5 Gender and Care Economy

The feminization of ageing and care work underscores the need for policies that value and redistribute unpaid care labor.

Formalizing the care economy — with training, certification, and digital platforms for care services — could unlock new employment opportunities, especially for women.

This aligns with UNESCAP’s emphasis on “gender-responsive ageing and digital inclusion strategies” and with Philippine commitments under the Magna Carta of Women and Digital Transformation Framework for Gender Equality.

7. Building the Silver Economy through Digital Inclusion

7.1 The Case for a Silver Digital Economy

By 2050, Filipinos aged 60 and above will comprise a significant market — for health tech, financial services, leisure, and lifelong learning. The “silver economy” can become a new growth frontier if the country invests in digital inclusion for older persons.

As the ITU’s Facts and Figures 2024 report emphasizes, universal connectivity remains the foundation of equitable growth — yet only 72% of people in developing Asia use the internet regularly. Ensuring that older citizens are digitally connected is not just social policy — it’s smart economics.

7.2 Designing Age-Friendly Digital Systems

- Simplify interfaces and authentication for seniors.

- Ensure cybersecurity and fraud protection for elderly users.

- Encourage intergenerational learning — digital literacy programs that pair youth with senior mentors.

This model, already piloted in Japan and Singapore, could become a Philippine best practice, blending Bayanihan values with digital citizenship.

8. Localizing the Demographic Agenda: The Role of LGUs and ICT Councils

Demographic transition doesn’t happen in Manila alone. Each region has a unique profile — some ageing faster than others due to migration patterns.

Local ICT councils, which Jocelle Batapa-Sigue has championed since 2008, can serve as demographic foresight and innovation hubs. They can integrate local data analytics, digital job generation, and inclusive training to ensure no province is left behind in the silver economy transition.

9. Technology and Governance: Preparing for an AI-Enabled Future

According to the International AI Safety Report (2025), nations must balance innovation with responsible governance to ensure AI benefits society equitably.

For the Philippines, this means:

- Embedding AI ethics and governance in all sectors.

- Encouraging AI for public good — from health diagnostics to smart agriculture.

- Building local AI talent pipelines through partnerships between government, academe, and industry.

These align with the UN System White Paper on AI Governance (2024), which calls for inclusive, globally coherent governance models that consider developing countries’ perspectives.

Strategic Takeaways

- The Philippines is entering a make-or-break decade.

The demographic dividend is still open, but closing soon. Policies in education, health, and jobs must converge to maximize productivity now. - Ageing will reshape every sector.

Health, housing, labor, and digital policies must anticipate a doubling of the senior population by 2050. - Women’s longevity changes the equation.

Gender-sensitive pension, care, and digital inclusion programs are essential for equitable ageing. - Digital transformation is the lever for demographic resilience.

The same technologies driving youth employment can empower older citizens — if designed inclusively. - Local governments must lead.

LGUs, empowered with data and digital tools, can localize solutions — from rural telehealth to elder entrepreneurship.

Turning Transition into Transformation

The Philippines’ demographic story is not destiny — it is a choice.

We can age with dignity, productivity, and digital empowerment if we act decisively today. The data from ESCAP is not a warning — it is a map. A map pointing toward a future where Filipinos live longer, work smarter, and connect across generations through technology and empathy.

Harnessing the demographic dividend while preparing for the silver economy is not a contradiction — it’s a continuum. It means building a society where every stage of life — from youth to old age — is valued, supported, and digitally included.

If the country invests wisely now — in people, innovation, and inclusion — the Philippines can transform its demographic transition into a “demographic transformation”: one that powers sustainable, equitable, and human-centered development for decades to come.

Post Scripts from Chiang Mai: My Personal View

When the invitation from the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific arrived, it felt like a call to service wrapped in a moment of urgency. Two super typhoons were battering the Philippines at the time, as if nature itself wanted to remind us how fragile and interconnected our world has become.

Their program highlighted a three-day workshop focused on enhancing digital literacy for older persons across the Asia-Pacific. This was not just another regional event. It was part of a much larger effort—one tied to demographic shifts, digital risks, social inequality, and the urgent need to build societies that protect and empower older citizens. And as the Philippines enters its demographic transition, with ageing accelerating by 2028 toward a more pronounced shift by 2040, our participation in global dialogues like this is no longer optional. It is essential.

So I packed my bags and flew to Chiang Mai—a city that would soon show me how wisdom, culture, technology, and care for older persons can live together beautifully.

The moment I stepped outside the airport, Chiang Mai greeted me with a softness that Manila rarely allows. The light was warm, the air gentler, and the mountains stood like timeless guardians. Thailand’s northern capital is a place where ancient temples coexist with digital cafés, where elderly citizens walk freely and confidently, and where society’s respect for its elders is woven into everyday life.

This gentleness is deceptive, though. Beneath it lies a deep, unspoken intelligence. Chiang Mai does not rush—but it never stops moving forward.

It was the perfect city to host a conversation about ageing, technology, and digital inclusion.

The Gathering of a Region

The workshop opened on 18 November 2025 at the Grand Ballroom of the Chiang Mai Marriott Hotel, gathering policymakers, academics, civil society leaders, innovators, and UN experts from across the Asia-Pacific. The organizers set the tone immediately.

The opening remarks came from:

• Mr. Srinivas Tata, Director of the Social Development Division of ESCAP

• Mr. Ye Xuenong, China’s Permanent Representative to ESCAP (via video)

• Ms. Ora-orn Poocharoen, Director of the School of Public Policy at Chiang Mai University

Their messages revealed a shared theme: the digital divide is not just about connectivity—it is about opportunity, dignity, and the ability of older persons to live meaningful lives in a fast-changing world.

Sabine Henning, Chief of ESCAP’s Sustainable Demographic Transition Section, presented the objectives and the program for the next three days. Her deep expertise in ageing, migration, and demographic transitions—shaped by nearly 30 years of UN work—gave weight to every idea she shared.

Delegates from Cambodia to Korea, Vietnam to Kyrgyzstan, Laos to the Maldives, India to Japan and of course the Philippines—all of us introduced our roles.

The Asia-Pacific: A Region Growing Older and More Unequal

The first session focused on population ageing and the grey digital divide—an eye-opening exploration of who our region has become.

Sabine Henning and Napaphat Satchanawakul presented ESCAP’s demographic overview. Their data showed how countries everywhere are experiencing rapid ageing—Japan and Korea at the forefront, Thailand and Vietnam accelerating, China shifting dramatically, and the Philippines beginning its own sprint toward an ageing population.

According to ESCAP’s regional population data, the Asia-Pacific has tens of millions of older persons whose lives and opportunities are shaped by technology—yet many lack the digital skills or confidence to participate in a digital society.

This reality hit me deeply. For years, I have watched how digital transformation in the Philippines tends to be discussed as something modern and exciting—a wave of progress that will naturally benefit everyone. But the truth is far more sobering: without deliberate intervention, digital transformation can widen inequalities, deepen exclusion, and leave older persons behind at the worst possible time.

China’s own presentation, led by Professor Cheng Yuan of Fudan University, showed how even a digitally advanced country struggles with older persons’ digital access and confidence.

Then Robert de Jesus, representing ESCAP’s APCICT office, delivered a message about empowering women through digital transformation, reminding us that older women in rural and low-income communities are among the most digitally excluded groups in the world.

The Q&A that followed was striking not because of the questions, but because of the shared tone: every country, regardless of development level, faces the same fundamental challenge.

Session 2: Tools, Pilots, and the Start of Practical Solutions

After the group photo and break, the workshop resumed with discussions about the ESCAP Digital Literacy Toolkit and the pilot results from Cambodia, India, and Vietnam.

As moderator of this session, I had the privilege of guiding the conversation. It was the first moment where our collective efforts moved from data and theory to tools, stories, and lived experiences.

ESCAP’s team showcased the toolkit—designed for older persons, grounded in behavioral insights, and adaptable to the diverse cultures of Asia-Pacific. The toolkit’s structure draws from extensive testing and consultation. Its modules focus not only on basic digital skills but also on confidence-building, motivation, online safety, and trust.

Cambodia shared how its ageing communities embrace digital learning when supported by local associations.

India demonstrated how grassroots approaches and local mentors accelerate digital adoption among elders.

Vietnam’s presentation, delivered by Le Minh Duc, highlighted how digital literacy becomes powerful when combined with intergenerational exchange and social enterprise innovation.

Each story revealed a similar truth: older persons thrive when digital learning is delivered with empathy, patience, and cultural alignment.

In many ways, this resonated with my own experience in the Philippines, where seniors often learn best through barangay-level sessions, familiar faces, and gentle coaching rather than technical lectures.

Conversations and Shared Realities

During meals, conversations flowed effortlessly. Representatives from HelpAge International, AARP, Thailand’s YoungHappy community, Malaysian and Indian universities, and various government ministries shared their views. I was struck by how everyone recognized the same problems: the cost of devices, the fear of “breaking” a mobile phone, the speed of app updates, and the shame that older persons sometimes feel when asking for help.

Ageing, I realized, equalizes us all—but digital inequality divides us sharply.

After lunch, the program shifted to national policies, with countries like Lao PDR and the Maldives sharing their strategies to support older persons.

Each country had unique challenges, but one insight kept emerging:

digital inclusion is no longer merely an ICT agenda—it is a national development, social welfare, and ageing policy priority.

Chiang Mai: More Than a Venue

That first evening, as I walked from the hotel to a nearby temple, the city seemed to whisper its own quiet lessons.

Elderly Thais moved comfortably within the city’s digital ecosystem—scanning QR codes for payments, navigating food apps, and consulting online maps. At the same time, they retained their cultural rhythms: lighting candles at temples, weaving baskets at the markets, chatting with grandchildren in cafés.

Chiang Mai showed me that digital inclusion does not erase tradition—it strengthens it, keeping older persons connected to the world while preserving the identity of their communities.

With these reflections, I returned to my hotel that night knowing that the next day would bring deeper conversations, more complex questions, and richer exchanges. And it did.

The Philippine Narrative: Leadership, Lessons, and the Digital Future of Ageing

By the second day of the workshop, the discussions in Chiang Mai had already moved from diagnosis to direction—from understanding the problem to building the solutions. The atmosphere became more intense, more analytical, and more ambitious. Delegates were no longer merely exchanging experiences; we were co-creating pathways toward a future where older persons are not left behind in an increasingly digital world.

It was during these more technical, ecosystem-oriented sessions that my intervention for the Philippines became deeply relevant. Years of work across national government, ICT councils, communities, and legislative interfaces have shaped my understanding of digital inclusion—not as a single program, but as an ecosystem whose strength depends on its weakest part. Digital inclusion for older persons, in particular, demands coordination, policy clarity, practical support, and compassionate design.

Day 2 reflected exactly this shift. Morning discussions explored local innovations and intergenerational strategies, while Session 5 placed a spotlight on how community-level practices can scale into national systems. The challenges became more complex, touching on AI-era risks, digital health ecosystems, and the ethical design of technologies used by older persons.

This was the point at which my Philippine presentation took center stage.

My Presentation: Bringing the Philippine Story to the Regional Table

My contribution to Session 4, scheduled for the afternoon of Day 1, was an opportunity to weave together not just research or policy, but lived experience—stories from barangays, senior centers, digital literacy caravans, and countless conversations with older Filipinos who often feel left behind by the pace of digital change. The programme described my role formally but in truth, what I delivered was the heart of the Philippine journey toward digital inclusion.

I began with the reality: the Philippines is at a critical demographic juncture.

According to ESCAP’s population sheet and our national demographic projections, the Philippines is currently enjoying its demographic dividend, but this window closes fast. By 2028, we begin our transition into an ageing society, and by 2035–2040, older Filipinos will represent one of the most vulnerable and economically constrained demographic groups.

These changes reshape everything—our labor market, social protection systems, public health infrastructure, and, most urgently, how we integrate digital literacy and digital participation for those who did not grow up with technology.

Then I shared the number that always shocks audiences, no matter the country:

Only 6% of Filipino seniors aged 65 and above use the internet.

Another figure from the ESCAP briefing validated this concern:

Only 18% have even one basic digital skill.

unescap speech

These numbers are not simply statistics. They represent teachers who can no longer navigate digital benefits, retirees who struggle with online banking or government portals, grandmothers who cannot access telemedicine, widowed senior women who fear scams, and elderly farmers in rural communities who cannot enter the digital economy even if they want to.

I explained that aging in the Philippines is deeply multidimensional. It is shaped by geography, income inequality, gender, family dynamics, and the uneven distribution of digital opportunities. Rural provinces like Negros Occidental, North Cotabato, Sorsogon, or Antique experience digital exclusion very differently from urban centers like Manila or Cebu.

In all these contexts, digital literacy is not simply an ICT agenda—it is tied to survival, resilience, access to health, and the dignity of navigating modern life.

And then I said the line that became the anchor for my presentation:

Digital inclusion is therefore not simply about ICT—it is about ensuring older persons can thrive in a rapidly changing society.

This sentence, simple as it was, shifted the room.

The Philippine Policy Landscape: Many Actors, One Direction

From there, I moved into a deep explanation of the Philippine policy landscape. This was the beginning of what, in your notes, you called Slide 5, and it was essential to ground our story within the broader regional conversation.

The Philippines’ approach to digital inclusion for older persons is dispersed across several institutions.

The National Senior Citizens Commission (NCSC) leads policymaking for older persons, including digital empowerment and welfare integration.

The DSWD delivers frontline services, including community learning initiatives. LGUs provide barangay-level digital coaching and local hubs.

Digital governance agencies and public Wi-Fi implementers expand infrastructure and connectivity.

These agencies collectively shape an ecosystem where digital literacy programs, public Wi-Fi installations, e-government solutions, and senior-friendly interventions slowly create the backbone of a more inclusive digital society.

In my speech, I emphasized that this multilevel approach is necessary because digital exclusion among older persons is rarely caused by one factor alone. It is a knot of interconnected challenges—access, affordability, confidence, skills, cultural attitudes, and physical limitations.

The message I delivered was clear:

Our institutions now recognize that digital inclusion is foundational to building an age-friendly society.

The NCSC serves as the national anchor that keeps policies aligned and focused on digital inclusion as a rights-based entitlement. The Commission’s growing digital initiatives—training programs, onboarding sessions, rights-awareness campaigns, and direct coordination with both national agencies and LGUs—reflect a shift toward more structured, more unified support for senior digital participation.

I emphasized to the regional audience that this kind of national leadership is crucial to avoid fragmentation. Without a central guiding body, digital inclusion efforts risk becoming dispersed or uneven, leaving rural communities severely underserved.

The Digital Senior Citizen ID: A Milestone with Big Responsibilities

I introduced one of the Philippines’ biggest ongoing milestones:

the rollout of the Digital Senior Citizen ID through the eGovPH platform developed by DICT.

More than a million older Filipinos have already been onboarded, which is a monumental step. This digital ID streamlines benefits, reduces administrative barriers, supports digital service integration, and signals a national commitment to digital transformation.

But I made sure to raise a crucial point:

digitizing identification does not automatically mean inclusion.

Digital IDs can empower seniors—but only if paired with:

• training

• accessible design

• simplified interfaces

• stable connectivity

• person-to-person guidance

Otherwise, the very tools meant to empower seniors may inadvertently deepen exclusion.

For an audience filled with policymakers, researchers, and digital innovators, this reminder felt timely.

As I said during my presentation:

“A digital ID without digital skills will never result in digital inclusion.”

Partnerships Beyond Government: The Strength of Communities

In the Philippines, meaningful digital inclusion does not emerge from Manila alone. It emerges from community, collaboration, and civil society. I shared how non-government actors in the Philippines fuel the ecosystem:

Telecommunications companies conduct senior digital coaching nationwide. NGOs and CSOs create safe learning spaces for older learners.

Universities develop intergenerational mentorship programs.

Local communities create hubs where seniors can learn at their own pace.

These partnerships are powerful because they bring digital learning closer to home—making it more approachable, less intimidating, and more culturally grounded.

The lesson was clear: Digital transformation becomes age-inclusive only when communities co-design the solutions.

Digital Inclusion and the Sustainable Development Goals

I connected the dots to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), explaining that digital literacy for older persons is not a siloed issue but an SDG accelerator.

SDG 3 — Telehealth and digital health tools reduce geographic barriers.

SDG 4 — Lifelong learning becomes accessible when digital skills are present.

SDG 5 — Older women gain independence and empowerment.

SDG 8 — Older persons can continue economic participation through digital work.

SDG 10 — Digital inclusion reduces inequality and rural disadvantage.

SDG 17 — Partnerships become the backbone of digital ecosystems.

These connections resonated strongly with ESCAP’s own framing of digital inclusion, as laid out in the programme and thematic sessions of the workshop.

AI-Era Challenges: Beyond the Digital Divide

Towards the end of my intervention, I shifted to a more forward-looking discussion. Many participants were surprised—but deeply engaged—when I explained that digital literacy for older persons will soon intersect with artificial intelligence in profound ways.

AI systems—from banking chatbots to government platforms—are becoming default interfaces. But these systems are often not designed with elders in mind. Their complexity, rapid evolution, and lack of transparency can alienate those without strong digital confidence.

I emphasized that unless AI accessibility is integrated into policy frameworks now, older persons could face an AI-based digital divide worse than anything we have seen in the past decade.

This statement sparked one of the most dynamic Q&A exchanges, with delegates discussing:

• human oversight in automated decision-making

• safeguards against bias

• how seniors interact with AI interfaces

• the need for explainable, senior-friendly AI

• the risk of algorithmic exclusion in government systems

This aligned with the insights in my speech: that digital transformation must be ethical, inclusive, and grounded in human rights—especially for the elderly, women, and rural populations. In that moment, I realized something powerful:

Every country was carrying the same hope—that no older person would be left alone in a digital world they didn’t ask for but must now navigate.

Wisdom Across Generations: Lessons, Innovations, and the Road Ahead

The final day of the UNESCAP Regional Workshop in Chiang Mai brought together every thread of the conversation—policy, practice, innovation, community models, demographic urgency, gender inclusivity, digital safety, and the future of ageing in a world increasingly mediated by technology. As delegates gathered once more in the Grand Ballroom, there was a quiet but unmistakable sense that the region was moving toward a shared understanding: We cannot build the digital future unless it includes older persons.

From the first plenary to the closing synthesis, every speaker emphasized that digital literacy for older persons is not a small program, not an ICT add-on, but a core requirement for achieving inclusive development in the Asia-Pacific.

This final section of the article explores the innovations, reflections, and commitments that emerged from the workshop’s last day and from the deeper lessons I personally carried home—not just as a participant, but as an advocate who has spent decades building ecosystems for digital inclusion.

Intergenerational Approaches and Community Innovation

The second day opened with a powerful session on reaching older persons in the community through intergenerational learning and local innovations.

This session—moderated by Sawang Kaewkantha of the Foundation for Older Persons’ Development—highlighted the central truth that older persons learn best through connection, not isolation.

The first presentation, delivered virtually by Professor Pei Lee Teh of Monash University Malaysia, dug deeply into the behavioral patterns of older adult tech users. Her data illustrated that older persons rely heavily on relational cues—trust, repetition, familiar faces, and simple instructions—far more than younger digital natives. She explained how interface design must be predictable, familiar, and non-intimidating.

This was followed by a compelling presentation from HelpAge India. Sonali Sharma introduced their community-based digital inclusion model, showing how older persons gain confidence through safe spaces in neighborhoods, often led by trusted local volunteers.

Vietnam then delivered a standout presentation. Tran Bich Thuy, Country Director of HelpAge International in Vietnam and Director of VIOBA Social Enterprise, demonstrated how Intergenerational Self-Help Clubs (ISHCs) have been quietly reshaping the digital landscape for older Vietnamese. These clubs serve as community centers where elderly people and youth learn from each other—young people teaching ICT skills, older persons passing down cultural wisdom and resilience strategies shaped by decades of life experience.

The presentation by Thailand’s own YoungHappy CEO, Charkhris “Gap” Phomyoth, added another layer. His explanation of the Community Digital Coach Model showed how seniors in rural Thailand can successfully learn smartphones, online transactions, and safety techniques when supported by senior-friendly social enterprises that blend digital platforms with warm human interaction.

As I listened to these community practices, I saw clear parallels to the Philippines: the barangay system, Tech4Ed or Digital Transformarion Centers, our intergenerational volunteer groups, and university-led digital literacy sessions all possess similar DNA.

The message that grew louder as the session unfolded was simple:

Digital literacy becomes sustainable only when communities take ownership.

Digital Health Ecosystems and Innovative Lifelong Learning

Later in the afternoon, the conversation shifted toward ecosystems.

Japan’s representative, Associate Professor Myo Nyein Aung from Juntendo University, discussed emerging digital health platforms tailored for older persons. His presentation looked ahead to a future where digital health records, remote care, early detection tools, and age-friendly medical apps could reduce health burdens and improve daily life for seniors.

This was complemented by Thailand’s MEDEE Digital School, presented by Nuttee Suree of Chiang Mai University, whose bio in the workshop documents reads like a blueprint for age-inclusive educational innovation.

His MEDEE project, which developed a LINE-based digital learning ecosystem for seniors, demonstrated what is possible when a university aligns mission, technology, and compassion. MEDEE’s achievements—winning multiple international awards and enabling thousands of seniors to earn supplementary income during the pandemic—showed how powerful it can be when institutions activate their full potential for digital inclusion.

This resonated strongly with me. In the Philippines, universities hold immense untapped potential. Many already operate as lifelong learning hubs, but their role in senior digital literacy can expand greatly. As we move into the final years before our ageing transition begins, universities can become the brain centers and innovation anchors for communities nationwide.

Day 3: From Knowledge to Action

The last day of the workshop brought every insight together in a series of interactive working groups. This part of the program, carefully designed by ESCAP and Chiang Mai University, featured five key thematic groups:

Infrastructure, skills and confidence, motivation and usage, safety and trust, and policy integration—each guided by regional experts.

I joined conversations that were intense and practical. We discussed how to adapt the ESCAP Digital Literacy Toolkit for diverse environments—from mountain villages in Lao PDR to urban neighborhoods in Malaysia, from island communities in Indonesia to senior cooperatives in Vietnam and the Philippines.

Groups debated over questions that policymakers often avoid:

What happens to digital learning when a senior has limited mobility?

What about those who live alone?

What if an older person is afraid of making a mistake because “b baka masira ang cellphone”?

How do we address shame, fear, and loss of confidence—emotions that often shut down learning before it even begins?

Safety, trust, and digital rights became a major topic. This theme was especially powerful considering how easily older adults fall prey to online scams, fraudulent investment schemes, social engineering attacks, and misinformation. The Philippine experience—where text scams remain rampant—became a relatable example to several countries who admitted facing the same vulnerabilities.

One of the most meaningful insights raised in my group was this:

Older persons need not only digital skills, but digital confidence.

This distinction became a recurring theme throughout the day.

The Power of Context: Localizing Solutions for the Asia-Pacific

While walking around the ballroom during the working group breakout, I reflected on how each country brought distinct approaches shaped by its cultural, economic, and geographic context.

Cambodia emphasizes community elders’ associations, which bridge traditional respect structures with modern digital learning.

India scales through massive civil society networks and low-cost community hubs. Vietnam relies on intergenerational clubs and social enterprises. Japan focuses on digital health, robotics, and smart ageing ecosystems. Thailand thrives through social enterprises like YoungHappy and university-driven programs like MEDEE. China integrates vast data systems and demographic projections into national ageing strategies. Malaysia builds behavioral research into interface design and curriculum development.

The Philippines, meanwhile, sits at a unique intersection:

a youthful population that will quickly transition into ageing, a heavily diaspora-influenced digital culture, strong LGU structures, barangay-level governance, and an archipelagic geography that amplifies the challenge of reaching remote seniors.

This diversity across Asia-Pacific reinforced a bigger truth:

Digital inclusion strategies must never be copy-paste templates. They must be grounded in local culture, community structures, and the lived realities of older persons.

My Walks Through Chiang Mai: The City as a Teacher

Whenever sessions ended for the day, I walked around Chiang Mai—not as a tourist, but as someone seeking quiet space to internalize the full weight of the workshop. Chiang Mai taught me that ageing does not have to be framed as decline. It can be a continuation of participation—if the environment supports it.

Its seniors are visibly integrated into daily life. They are not tucked away; they are present. And because they are present, digital literacy becomes a natural part of living, not a technical project.

This realization deepened my sense of urgency for the Philippines.

Our seniors deserve the same ease and confidence.

A Region’s Shared Commitment

During the final plenary, the atmosphere felt both hopeful and serious. Delegates reviewed the outcomes of the working groups, shared reflections on the ESCAP toolkit’s implementation, and discussed next steps for adapting regional frameworks to national landscapes.

It was here that the collective voice became clear: Digital inclusion for older persons is no longer optional. It is a moral, economic, and developmental imperative.

My Personal Reflections: What This Workshop Means for the Philippines

As I prepared to leave Chiang Mai, my heart felt full. This was not just a workshop. It was a mirror held up to our region—and to myself.

If the Philippines is to truly embrace age-inclusive digital transformation, several realizations must guide us:

One: Digital inclusion must be human-centered.

Older persons learn differently—not more slowly, but differently. Our teaching methods must evolve.

Two: Intergenerational learning is powerful.

Youth and seniors learning together builds empathy, trust, and motivation.

Three: Institutions matter.

NCSC, LGUs, universities, ICT councils, and digital governance bodies must work together seamlessly.

Four: Technology alone cannot solve exclusion.

Infrastructure, apps, and digital IDs mean little without skills, confidence, and cultural relevance.

Five: AI will reshape digital inclusion.

Unless senior-friendly AI is embedded early, older persons risk facing a new, deeper digital divide.

Six: Digital inclusion is tied to rights.

It is no longer just about convenience. It is about safety, access, health, participation, and dignity.

And lastly:

Seven: We must act quickly.

The Philippines’ ageing transition is not in the distant future. It is beginning now.

A Path Forward: Building an Age-Inclusive Digital Nation

As I look ahead, my commitment to this advocacy grows even stronger. The lessons from Chiang Mai reaffirm what I have believed for years:

The Philippines must invest deeply—strategically, compassionately, and consistently—in digital inclusion for older persons.

This means:

• Empowering LGUs as the backbone of community-based digital learning.

• Strengthening the role of NCSC as the central coordinating agency.

• Building senior-friendly interfaces across all e-government services.

• Expanding public Wi-Fi and device access for low-income households.

• Mobilizing universities to become hubs for lifelong digital learning.

• Embedding AI ethics, transparency, and age-inclusion into all digital policies.

• Nurturing intergenerational mentorship programs nationwide.

• Creating safe spaces for seniors to practice digital skills without judgment.

• Working with telcos, CSOs, and private sector innovators to reach every barangay.

But more than structures and programs, age-inclusive digital transformation requires a cultural shift.

We must build a Philippines where older persons are seen not as burdens, but as bearers of wisdom, culture, and intergenerational identity—where technology becomes a bridge rather than a barrier.

Asia-Pacific: A Region Moving Forward Together

Chiang Mai taught me many things, but one thought stays with me strongest:

A society’s strength is measured by how it supports those who came before us.

As the Asia-Pacific enters a new demographic era, as digital systems expand with breathtaking speed, and as AI reshapes daily life, we must ensure our elders are not simply observers of the digital world—but empowered participants.

The workshop’s final message captured this perfectly:

“A digital society is only truly advanced when every generation can move forward together.”

unescap speech

This is the future I want for the Philippines.

This is the vision I will continue to fight for.

PHOTO GALLERY

Leave a comment