I was honored to speak at the Legal Education Technology and Inclusion Summit 2025 held on November 13 to 14, 2025, at the University of Santo Tomas, Manila with the transformative theme “DIGITAL LawEd: Driving Innovation and Growth through Inclusive Technology and Access to Legal Education.”

The Summit was organized by the Legal Education Board (LEB) under the leadership of Chairperson Atty. Jason R. Barlis. It served as an important platform for convening educators, legal practitioners, technology leaders, and inclusion advocates to examine the evolving landscape of legal education in the Philippines. As the sector responds to the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence, digital learning, and emerging technologies, the event provided a valuable opportunity for collective reflection and strategic collaboration. I had the privilege of delivering the Plenary Culminating Lecture on November 14, 2025 on the topic – “Teaching the Nation How Law and Technology Shape an Inclusive Philippines,” where I was invited to deliver the closing plenary speech. I shared insights from my work in AI governance, digital inclusion, and the development of innovation ecosystems across the country. I deeply appreciated the Legal Education Board’s commitment to strengthening accessibility, ethical digital practices, and institutional readiness—efforts that are essential to ensuring that technology enhances the quality, equity, and reach of legal education. It was a meaningful experience to engage with leaders and advocates dedicated to shaping a more inclusive, future-ready legal education system for the nation.

SPEECH DELIVERED By Jocelle Batapa-Sigue, JD

Former Undersecretary for ICT Industry Development, DICT

Board Member, ITU Digital Innovation Board

Lead Convenor, DIWA – Digital Innovation for Women’s Advancement

Opening

Good afternoon to everyone — to my fellow lawyers, educators, deans, professors, and friends in the noble service of nation-building — it is an honor to speak to you today about two forces that are profoundly reshaping the world: Law and Technology. Thank you Dean Barlis and the Legal Education Board this very valuable opportunity.

Allow me to begin not with a legal theory, but with a personal story.

When I was a little girl, I would sit in the corner during family gatherings, watching and listening as the adults talked about politics, public affairs, and the latest stories from our community. What struck me, even then, was that it was always the men who led the discussion — their voices loud and confident — while the women, whose insights I knew were just as sharp, would sit back and listen quietly.

So one day – I asked my father – when I grow up – what profession should choose – which would give me – a woman the chance to speak my mind?” What profession would allow women to speak — to share their thoughts about politics, about life, about the country — and be listened to with equal respect?

Then he showed me this picture. “I know one woman who can stand up to any man in a conversation, anytime, anywhere. You should follow her profession.”

The late Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago and Senator Franklin Drilon – were my father’s classmate in AB Political Science in UP. And he would always prod me to follow their footsteps since he never got the chance to pursue law despite being one of the most quick-witted and eloquent in his class.

The rest is history – I dreamt of becoming a lawyer at age 7.

At the age of nine – when my mother died due to childbirth and saw my father struggling to write a narrative of what will supposedly become a complaint for medical malpractice against the doctor – my resolve to become a lawyer deepened.

While taking up law – I also chose to be a working student in field that also gave me the opportunity to speak and deliver information – I worked part time as news writer for a local newspaper, and a TV reporter for the local GMA and ABS CBN TV stations in the 90s – all in Bacolod.

But when it was time to take the bar, I focused on one thing – to achieve this profession that would give me a bigger voice.

Young as I was then – I believed the law was the most powerful tool to make sense of the world — to turn conviction into clarity, and clarity into change. So at 25, I became a lawyer.

I spend my first years as a lawyer trying to find a husband – thank God I found one who is also a lawyer, a former prosecutor and NBI agent. Now I can say – I am safe and very secured – to speak. Eventually I realized being a lawyer is but a good staring point to find more ways to serve – and so I joined politics and served for 9 years as Bacolod City Councilor. I have thought in my alma mater – the College of Law of the University of St. La Salle – have mentored over 200 lawyers an our 3 deans attended this summit Dean Ralph, Dean Rosanne and Dean Rhodora.

From there I harnessed my passion for understanding Information and Communications Technology – because this was the only committee together with the committee on women – that was given to me by majority and minority blocs – back then I was independent candidate.

This very same ICT committee in 2004 – allowed me to create strategies to grow digital jobs in my city. I helped craft documents to create the ICT council – which embodies the formula – MAGIC – Making Academe Government Industry Collaborate – MAGIC to create jobs and opportunities. A formula which I was able to share in my speeches and panels to about 25 countries for the last 20 years – and hopefully counting.

Eventually, I helped co-create a national organization of all ICT councils – which gave me the opportunity to help other ICT champions to create more digital jobs beyond Metro Manila.

For 3 years as part of my role at the DICT – I was blessed to speak before many countries represented by men at the ITU council– and they all listen.

That journey — from a small city in the Visayas to serving as Undersecretary for ICT Industry Development at the DICT, Board Member of the ITU Digital Innovation Board, and advocate for digital jobs, women in technology, and countryside innovation — I have learned one enduring truth:

Legal knowledge is not static. It is the architecture of innovation.

It is the bridge between the law and the future — between what is and what can be.

Part I. The Digital Pulse of the Nation

Let’s start with the landscape.

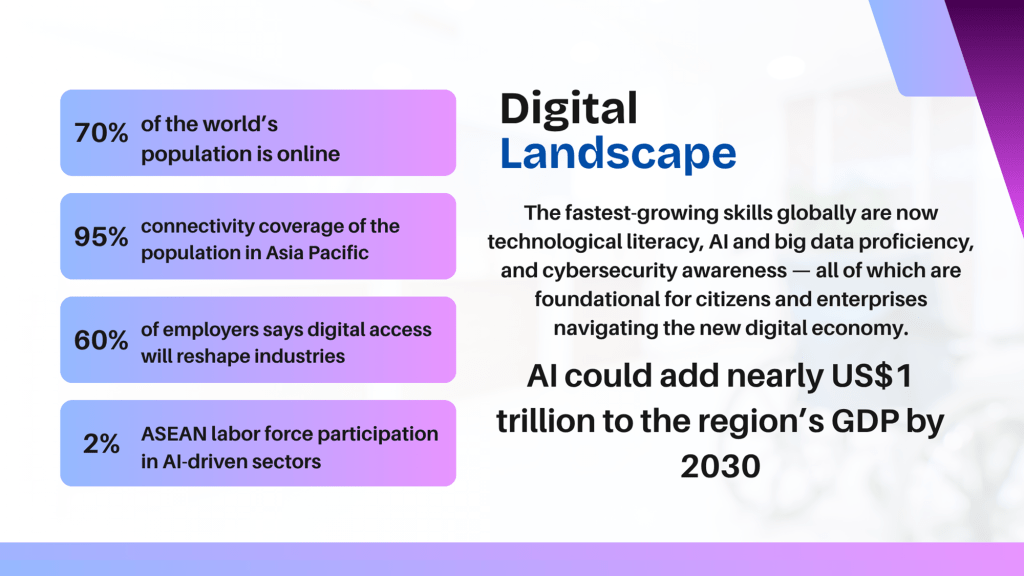

According to the ITU 2025 State of Digital Development – 5.6 billion people connected globally, representing nearly 70% of the world’s population. Still, that leaves 2.4 billion people excluded — a gap that reflects not only infrastructure challenges, but persistent inequities in affordability, literacy, and access.

Across the Asia-Pacific, connectivity now covers over 95% of the population, but as the ITU reminds us, coverage does not mean connection. There are economic and cultural constraints that limit participation fo many sectors in the digital sphere.

Here in the Philippines, the digital space is strong and growing faster each year. Fiber-optic networks, satellite technologies, and community-driven Wi-Fi initiatives are expanding nationwide. Municipalities, cooperatives, and local enterprises are finding innovative ways to deliver connectivity — from shared broadband in coastal communities to localized digital hubs that enable online learning, e-commerce, and e-governance. But even as physical access improves, the real measure of progress lies in how people use connectivity to enhance their lives — in learning, livelihoods, and local innovation.

The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2025 underscores this transition: digital access is projected to be the most transformative global trend toward 2030, with 60% of employers saying it will reshape their industries. The fastest-growing skills globally are now technological literacy, AI and big data proficiency, and cybersecurity awareness — all of which are foundational for citizens and enterprises navigating the new digital economy.

The Harnessing AI: Transforming Southeast Asia’s Workforce (2025) study estimates that AI could add nearly US$1 trillion to the region’s GDP by 2030 — a 13% uplift — but achieving that potential requires an AI-ready workforce. While the share of AI-skilled talent in Southeast Asia has tripled since 2016, it still represents less than 2% of the labor force, signaling a vast need for skilling and inclusion.

Meanwhile, the AI for All: Building an AI-Ready Workforce in Asia-Pacific (2025) initiative, supported by Google.org and the Asian Development Bank, highlights that only one in five workers in developing Asia currently receives digital or AI-related training. It advocates for a “just AI transition” — ensuring that women, youth, and rural workers can meaningfully participate in the emerging digital economy.

We are no longer asking whether the Philippines is online — we are asking who benefits from being online. Connectivity is the foundation of opportunity, but inclusion is its true measure.

An inclusive Philippines is not merely wired — it must be digitally just:

one where every citizen, learner, and entrepreneur has not only access to the internet, but also the skills, confidence, and opportunities to use it well.

Part II. Education as the True Engine of Innovation

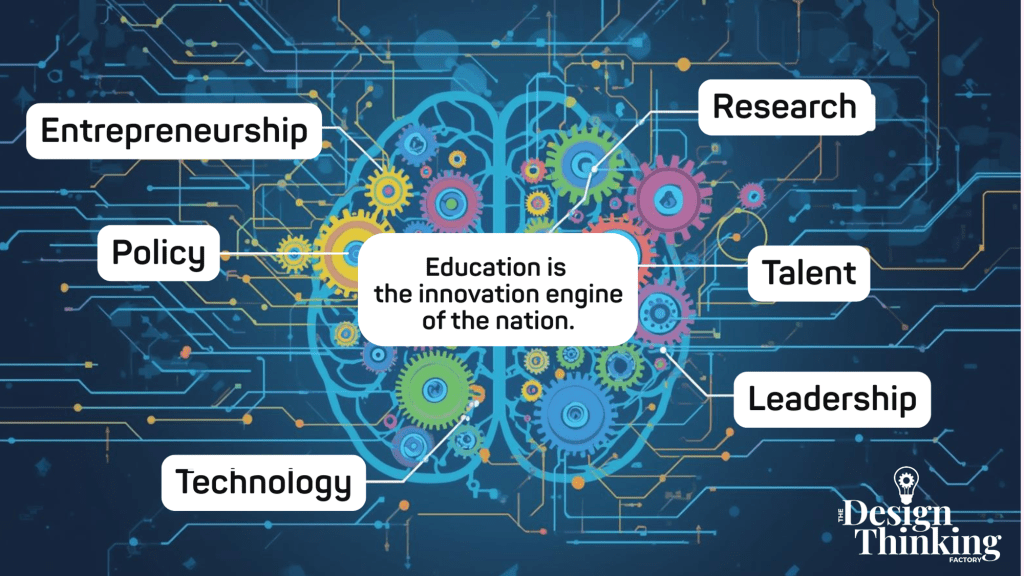

I believe and I have seen in many advanced nations that Education is not merely the foundation of innovation — it is the engine that keeps the nation’s innovation ecosystem in motion. Every new technology, policy, or enterprise draws its first spark from the human mind — and education is where that spark is nurtured into light.

Legal education, in particular, oils and fuels every gear of this innovation engine:

- Research turns legal theory into public policy, guiding how we regulate, protect, and promote innovation across emerging technologies.

- Leadership shapes ethical, foresighted leaders who can navigate both opportunity and risk in the digital economy.

- Entrepreneurship creates problem-solvers in governance and business who see law not as a constraint, but as a tool for equitable progress.

- Policy translates rights into inclusive systems that balance growth with fairness and accountability.

- Technology ensures innovation remains humane — governed by ethics, not just efficiency.

- Talent produces multidisciplinary professionals capable of bridging science, technology, and human values.

If education powers innovation, then legal education determines its direction.

In the age of artificial intelligence, data economies, and algorithmic decision-making, the law becomes not just a regulator — but an enabler of trust, safety, and societal cohesion. The International AI Safety Report (2025) warns that governance and ethics training must evolve alongside technical literacy, emphasizing systemic risk awareness, privacy, and accountability frameworks.

In the Philippines and across Southeast Asia, this vision takes on a special urgency. The Harnessing AI: Transforming Southeast Asia’s Workforce (2025) report estimates that AI could add US$1 trillion to regional GDP by 2030, but that its benefits will depend on an AI-ready workforce — one that blends digital competence with ethical discernment and policy insight.

Legal education must therefore expand its horizon: from statutes and case law to data governance, cybersecurity, and AI accountability. Our classrooms are where the nation’s future guardians of digital justice, cybersecurity, data privacy, and AI ethics are formed.

Each debate on intellectual property, each moot court on human rights in the digital space, and each policy lab on digital inclusion shapes the next generation of nation-builders — lawyers, policymakers, innovators — who will decide how technology serves humanity.

One of our greatest gaps today lies in the absence of focused, forward-looking policies for science and emerging technologies. Our next task, therefore, is to craft a robust AI governance framework — a policy architecture that many countries have already adopted, and which the Philippines must now build with foresight, ethics, and inclusivity at its core.

The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report (2025) emphasizes that the fastest-growing skills globally are not purely technical; they are analytical thinking, creativity, ethical judgment, resilience, and leadership — precisely the competencies honed by legal and interdisciplinary education. The Global Skills Taxonomy (2025) further calls for education systems that speak a common language of skills, linking learning outcomes directly to innovation ecosystems.

Legal education, then, must evolve as the conscience and compass of innovation — training not only those who interpret the law, but those who can shape the ethical infrastructure of the digital nation.

Part III. Balancing Innovation and Regulation: The First Role of Legal Education

I see four major roles of legal education and the law in the Digital Age.

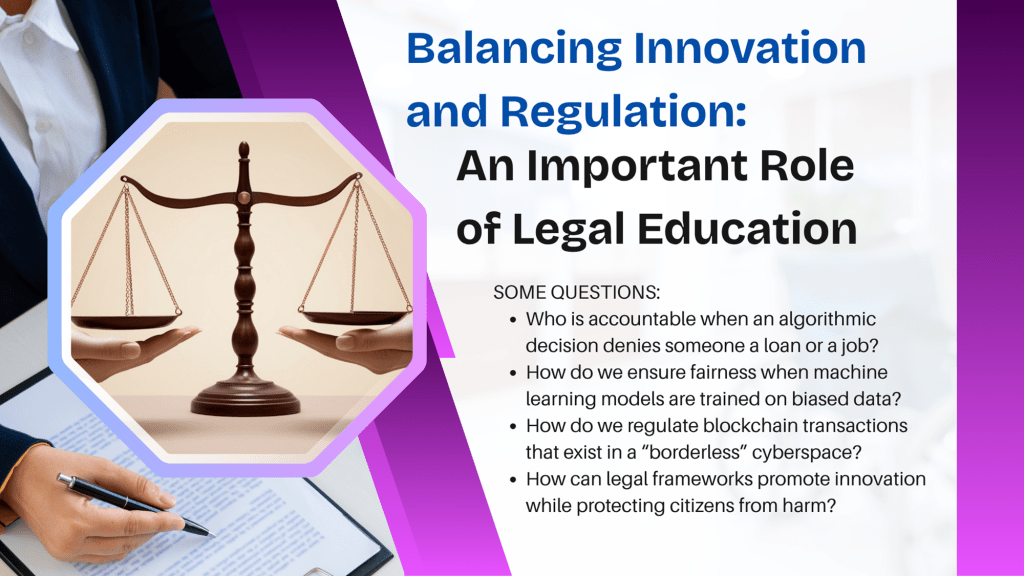

The first role of legal education in the digital age is to teach balance — the delicate equilibrium between innovation and regulation, between what technology can do and what society should allow it to do.

We now live in an era where artificial intelligence can draft contracts, blockchain can redefine trust, and data analytics can predict behavior with astonishing precision. The tools of progress are rewriting the rules of governance, commerce, and even justice itself. Yet, with every breakthrough comes a new dilemma: how do we protect human dignity, rights, and fairness in systems increasingly run by code?

Education is how we ensure that progress remains human-centered. It is the quiet power that keeps the gears of innovation turning — not blindly toward profit or power, but steadily toward justice, inclusion, and shared prosperity.

Every generation of lawyers has faced disruption — from industrialization to globalization. But the digital generation faces something unprecedented: technologies that evolve faster than the laws meant to govern them. AI systems that can reason, blockchain networks that defy borders, and data flows that transcend jurisdictions all challenge the very notion of sovereignty and accountability.

These emerging realities pose new questions that no legal textbook of the past could have prepared us for:

- Who is accountable when an algorithmic decision denies someone a loan or a job?

- How do we ensure fairness when machine learning models are trained on biased data?

- How do we regulate blockchain transactions that exist in a “borderless” cyberspace?

- How can legal frameworks promote innovation while protecting citizens from harm?

As someone who has worked on AI governance policy for the Philippines and contributed to international dialogues on AI safety and ethics, I have witnessed firsthand how rapidly the legal landscape must adapt. Around the world, legal systems are scrambling to keep up with technology — but the countries that will lead are those that train lawyers not just to interpret laws, but to design them for a digital future.

Regulation should never be seen as the enemy of innovation. When done well, it is its compass — guiding progress toward ethical, inclusive, and sustainable outcomes. Governance, law, and policy must evolve alongside technology, building public trust and mitigating systemic risks.

The UN White Paper on AI Governance (2024) calls for capacity-building across justice systems — recognizing that law schools, not just tech labs, are where digital trust begins.

AI offers tremendous promise in medicine, education, and law — from predicting disease to improving judicial efficiency. Yet it also poses profound risks: algorithmic bias, privacy breaches, manipulation of public opinion, and the erosion of accountability. If left unchecked, these risks could magnify inequality instead of promoting inclusion — deepening the very divides technology was meant to bridge.

That is why legal education must do more than teach statutes and precedents. It must cultivate foresight — training lawyers to anticipate the ethical, social, and legal implications of every technological advance. The lawyer of tomorrow must be part jurist, part ethicist, and part innovator.

They must understand AI ethics, data protection, digital identity, blockchain governance, and cybersecurity not as technical jargon but as the new vocabulary of justice. They will be called upon to draft the laws that govern autonomous systems, to argue cases involving algorithmic harm, and to ensure that technology serves humanity — not the other way around.

A lawyer who understands technology is no longer a niche specialist.

He or she is the guardian of the new public order — the architect of digital justice, ensuring that as we advance into the age of intelligent machines, we do not lose sight of the intelligent heart.

Legal education, therefore, stands at a new frontier — one where innovation and regulation must walk hand in hand. The classroom must become a laboratory of ideas where law students learn to balance rights with risks, speed with safety, and creativity with conscience. Because the lawyers we educate today will be the ones writing the digital social contract of tomorrow.

Part IV. Law Schools as Hubs of Policy Innovation

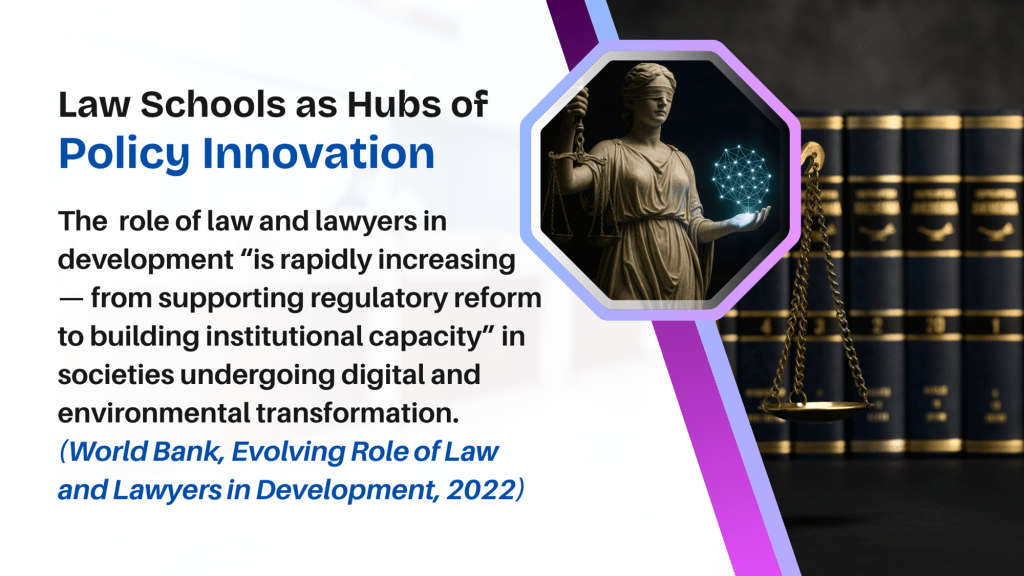

The second role of legal education in the digital age is to train lawyers not just as interpreters of law — but as policy innovators.

Policy innovation is not merely about drafting legislation or issuing regulations. It is the creative and strategic act of governance — the process of imagining the future and designing the rules that will make that future fair, inclusive, and sustainable.

In the Philippines, our legal education has produced some of the country’s most influential public leaders, legislators, regulators, and reform advocates. Many of our lawyers do not limit themselves to the courtroom; they step into the political arena, into public institutions, and into international negotiations, where they shape the national agenda through policymaking. From national statutes to local ordinances, lawyers form the backbone of our governance ecosystem.

In the era of digital and environmental transformation, the role of law and legal professionals is no longer peripheral—it is central. As highlighted by the World Bank, lawyers are moving beyond traditional litigation and contract work, toward enabling regulatory reform, institutional capacity-building, and supportive frameworks for inclusive development. For Filipino innovation ecosystems, this means the legal architecture must be agile, inclusive and forward-looking, enabling startup growth, bridging local-global digital jobs, and safeguarding both innovation and rights.”

But today, the integrity and vision of policymaking are being tested. Our country faces complex, cross-sector challenges — disinformation, climate risk, AI governance, data privacy, and economic inequality — yet we see a growing gap between policy power and policy wisdom. We have many policymakers, but far too few policy visionaries: individuals who lead with competence, moral clarity, and a long-term commitment to public good.

The World Bank’s 2025 event on “Innovative Legal Solutions to Development Challenges” explicitly mentions how legal professionals must engage with technology, regulatory reform, and development outcomes.

The Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs similarly stresses that the 21st-century lawyer must combine “core legal competencies” with leadership, ethics, and systems thinking to align law with social change.

This global view echoes what the visionary political scientist Harold Lasswell wrote as early as 1943: “The proper function of our law schools is to contribute to the training of policymakers for the ever-more complete achievement of the democratic society.” Nearly a century later, that message is even more urgent.

Nearly a century later, that message is even more urgent – the UN AI Governance White Paper (2024) stresses that capacity-building for policymakers and jurists is essential for shaping responsible global AI ecosystems.

If lawyers inevitably become policymakers, then law schools must become breeding grounds for effective, ethical, and visionary policymakers. Our students must learn not only what the law is but how the law becomes. They should understand how public policies are formed — through data, deliberation, and democratic participation.

According to the Institute for Government’s 2011 report Policy Making in the Real World, “policymaking is best understood not as a pristine, technocratic pipeline, but as a dynamic interplay of ideas, interests and institutions — and the democratic legitimacy of policy depends significantly on whether citizens understand and trust the processes by which decisions are made.”

When I served as Undersecretary for ICT Industry Development at the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT), this principle shaped every program I led. Policy was never written in isolation; it was co-created with the communities it would affect.

- We collaborated with industry leaders to develop the Philippine Startup Development Program, laying the groundwork for our innovation ecosystem and digital jobs agenda.

- We partnered with universities, ICT councils, and think tanks to align technology education with digital economy goals, ensuring that curriculum and policy evolved together.

- We worked with civil society, women’s networks, and global partners to develop AI governance and ethics frameworks rooted in Filipino values — transparency, accountability, inclusivity, and human dignity.

- We engaged local governments, MSMEs, and innovation hubs in formulating strategies for countryside digital jobs and equitable access to technology.

If law schools can teach this mindset — that policy is not politics but the design of systems that uphold justice and enable innovation — we will produce a generation of lawyers who build nations, not just cases.

Imagine every law school as a policy innovation laboratory: a space where students engage with real data, work with local officials to draft ordinances, study the social impact of regulation, and simulate decision-making under ethical and constitutional principles.

This aligns with the World Economic Forum’s Global Skills Taxonomy (2025), which calls for education systems to equip learners with interdisciplinary thinking, analytical reasoning, and societal awareness — all essential for policy leadership in the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

The Philippines urgently needs lawyers who can bridge law, ethics, and strategy — who can see policy as both instrument and inspiration. The current moment demands leaders who are as skilled in negotiation as they are in nation-building, as fluent in technology as they are in integrity.

Because policymaking is not just the task of government — it is the highest expression of public service. And law schools are where that calling begins.

If our classrooms can cultivate that balance — analytical rigor, moral courage, and creative governance — then we can once again trust our laws to reflect not just the letter, but the spirit, of justice.

Lawyers are already the nation’s most frequent policymakers.

It’s time our law schools acknowledge that reality — and embrace the responsibility to prepare them for it.

In a time when short-term politics too often overshadows long-term vision, the most radical reform we can make is this: to train lawyers who can think beyond elections — and legislate for generations.

Part V. The Lawyer in the Startup and Innovation Ecosystem

The third role of legal education in the digital age is to make the lawyer indispensable to innovation ecosystems.

Innovation cannot thrive without legal scaffolding. Every startup, no matter how visionary, needs the structure of law — from intellectual property protection to data compliance, from sound corporate governance to fair, transparent contracts. The most creative ideas collapse without the legal foundations that give them shape and legitimacy.

Lawyers are not barriers to innovation; they are the guardians of trust. They help founders transform ideas into enterprises by navigating regulation, structuring equity, protecting digital rights, and building transparent, accountable organizations. Without this legal backbone, innovation risks becoming exploitation — and startups struggle to move from potential to scale.

This message resonates especially today as we celebrate Philippine Startup Week — the country’s biggest annual platform for showcasing homegrown innovation. This celebration is not just about technology or entrepreneurship; it is about nation-building. It reminds us that creating more enterprises means creating more opportunities for jobs, inclusion, and growth. And when we combine legal knowledge and structured legal support with startup development, we multiply that impact. Legal guidance gives startups the stability they need to scale sustainably, to attract investment, and to operate with confidence both locally and globally.

When I helped develop the Philippine Startup Development Program and worked with various ecosystem stakeholders at the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT), I saw firsthand that policy, law, and innovation must evolve together. We didn’t just promote digital transformation — we built the legal frameworks to sustain it.

- We worked with startup founders, incubators, and venture funds to clarify regulations on investment, data privacy, and technology transfer, ensuring that Philippine startups could compete globally.

- We collaborated with local governments to integrate innovation-friendly provisions in local ordinances, enabling provinces to participate in the digital economy.

- We partnered with universities and lawyers to promote intellectual property education and legal mentorship programs for emerging innovators.

- And we aligned innovation policies with global ethical frameworks for AI, digital commerce, and data protection — ensuring that growth is not only profitable but principled.

From this experience, one truth became clear: when startups have access to legal guidance early on, they are far more likely to survive and scale.

That is why law schools must cultivate entrepreneurial lawyering — the mindset that lawyers are not gatekeepers, but enablers of innovation. Our curriculum must prepare students to work with startups, to understand their challenges, and to help them navigate laws that are often outdated or unclear.

We must integrate discussions in relevant courses on topics like:

- Technology and Innovation Law — covering intellectual property, data protection, cybersecurity, and AI regulation.

- Venture Capital and Startup Finance — teaching term sheets, due diligence, and investor agreements.

- Tech Transfer and Commercialization — bridging academia and industry.

- Digital Commerce and Cross-Border Transactions — aligning with ASEAN and global digital economy standards.

- Social Enterprise and Inclusive Innovation — encouraging frameworks that empower marginalized innovators.

As the WEF Future of Jobs Report (2025) reveals, the world’s fastest-growing skills are not just technical but ethical — analytical thinking, creativity, and governance literacy. These are precisely the competencies that lawyers bring to the innovation table.

They make sure equity is fair, intellectual property is respected, data is protected, and growth is inclusive. They ensure that innovation uplifts — not exploits.

Let us recognize that every new enterprise also needs a lawyer who believes in innovation. When legal education and entrepreneurship intersect, we create a force that drives national development. This is how a lawyer becomes not just a counselor of law, but a catalyst of the future.

Part VI. Legal Education for Digital Inclusion

Finally, the lawyer must be I the forefront of driving digital inclusion. Inclusion must always be part of innovation.

The International Telecommunication Union’s 2024 Facts and Figures Report reminds us that while 5.4 billion people are now online, 2.6 billion remain offline — and most of them are women, rural citizens, and marginalized communities. This reality is the very heart of my advocacy.

From countryside innovation, and from women’s leadership in ICT to the formation of ICT councils across the country, I have seen firsthand that digital transformation cannot be inclusive unless it is deliberate — unless it reaches the peripheries of opportunity.

When citizens are disconnected, they are not only excluded from the economy — they are excluded from education, from governance, and from their own voice in public discourse.

The World Economic Forum’s “Rise of Global Digital Jobs” (2024) report underscores that robust legal and regulatory ecosystems are critical to unlocking digital employment opportunities worldwide. Meanwhile, the ITU’s “State of Digital Development in Asia and the Pacific” (2025) finds that countries with stronger legal frameworks for data governance and innovation enjoy higher levels of investment and digital inclusion. This applies most urgently to rural and countryside economies, where startups often face not just market barriers, but regulatory uncertainty.

In the countryside, where digital jobs and innovation hubs are emerging, legal literacy is economic empowerment. Entrepreneurs who understand contracts, business registration, data protection, and consumer law are better equipped to attract funding, protect their IP, and compete in the digital economy. In my work promoting countryside digital jobs, I have witnessed how legal literacy among local innovators turns small towns into thriving tech communities. A single startup with sound legal grounding can spark a ripple effect of employment, investment, and community growth.

The United Nations Human Rights Council, as early as 2016, recognized internet access as essential to the exercise of freedom of expression and participation in public life. The UN’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation goes further — declaring that “digital inclusion is central to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals” and must be grounded in gender equity, ethics, and rights-based governance.

That is where legal education comes in.

We must prepare lawyers who understand that digital exclusion, online harassment, disinformation, and algorithmic bias are not technical problems alone — they are questions of justice and governance.

When our students learn that a data breach violates privacy rights, that online hate speech undermines dignity, and that biased AI systems can entrench discrimination, they realize that they have the power — and the duty — to uphold rights in cyberspace.

Law Schools as Enablers of Digital Justice

This is why I believe that every College of Law must now become an enabler of digital justice.

Law schools can lead the digital inclusion movement by integrating three transformative dimensions into their curriculum:

- Digital Literacy and Technology Law – Every future lawyer must understand data privacy, cybersecurity, e-commerce, and AI governance. The World Economic Forum’s Global Skills Taxonomy (2025) describes digital and data literacy as foundational competencies for all 21st-century professions — and this is doubly true for law, which regulates every other field that technology touches.

- Gender, Human Rights, and Digital Safety – We must teach the realities of technology-facilitated gender-based violence, or TFGBV.

A 2025 assessment of Philippine laws shows that while we have progressive statutes — the Cybercrime Prevention Act, the Safe Spaces Act, and the Anti-Photo and Video Voyeurism Act — they still do not capture the full scope of gendered harm online. Globally, the IREX Transform Digital Threats Report (2024) found that 40% of women in public life experience digital abuse intended to silence them. If we cannot protect women’s participation online, we weaken democracy itself. - Countryside Innovation and Access to Justice – Regional law schools can serve as digital empowerment hubs, working with LGUs, MSMEs, and local ICT councils to promote online safety, information access, and e-governance. This directly aligns with the my vision for countryside digital transformation — where innovation and opportunity are not confined to Metro Manila but shared across the archipelago.

In doing so, we transform our law schools from being ivory towers into innovation centers of inclusion.

Legal education must now become the architect of digital inclusion — embedding technology law, gender justice, and rural empowerment into its framework — so that every future lawyer becomes a defender not only of rights, but of equity in the digital age.

Part VII: Recommendations

Understanding these new roles and moving forward – I have some recommendations:

1. Curricular Reform: Teaching Law in the Age of Intelligence

Our law schools must be future-ready. That means embedding courses in AI ethics, digital law, cyber governance, blockchain regulation, and design thinking — not as electives, but as essentials.

The International AI Safety Report (2025) warns that AI systems are now capable of autonomous reasoning and decision-making, posing risks of bias, misinformation, and accountability gaps. Legal professionals must therefore understand not just what AI does, but how it decides — because in the future, many decisions that affect rights and livelihoods will be made with AI’s assistance.

Design thinking, meanwhile, equips law students to approach complex policy and ethical problems with creativity and empathy.

It encourages them to ask, “Who is affected? What problem are we solving? How can the law empower people rather than control them?”

By teaching law through innovation pedagogy, we cultivate graduates who are not just compliant thinkers — but creative policymakers.

2. Research Hubs: Building Knowledge for a Digital Republic

The creation of Law and Technology Research Hubs — think tanks that bridge academic research with national policy. Law schools must serve as knowledge engines for the country’s digital transformation.

These hubs can:

- Study how data governance, digital inclusion, and AI ethics affect Philippine society;

- Contribute to legislation on privacy, cybersecurity, fintech, and digital trade; and

- Collaborate with global networks such as the ITU Digital Innovation Board, the UNESCO Global Policy Forum, and the World Economic Forum’s Center for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

When law schools conduct research on how emerging technologies intersect with rights and governance, they become co-authors of the nation’s policy evolution.

Imagine if every major law school in the Philippines contributed similar research — producing the intellectual blueprints for a digital, inclusive Republic.

3. Community Immersion: Turning Legal Aid into Digital Justice

The third is community immersion.

Traditional legal aid clinics have long provided free legal services — but in the digital age, they can evolve into Digital Justice Centers.

Imagine clinics that don’t just handle domestic or labor cases, but also:

- Teach barangay leaders about data privacy and cybercrime;

- Assist women facing online harassment or image-based abuse;

- Help small entrepreneurs register digital businesses or protect intellectual property; and

- Educate citizens about their rights and responsibilities online.

These digital justice centers would bring the law to where it’s needed most — the frontlines of digital inclusion.

This is in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goal 16, which calls for “peace, justice, and strong institutions.”

Access to digital justice ensures that every Filipino, regardless of geography, can participate safely and confidently in the digital economy.

When we reimagine legal clinics as digital empowerment platforms, we transform community service into community innovation.

4. Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Law in Conversation with Science

Fourth is interdisciplinary collaboration.

Legal education must no longer stand in isolation. The world’s most complex problems — from cybersecurity to AI governance, from data privacy to environmental tech — require collaboration between lawyers, technologists, scientists, and entrepreneurs.

Law schools must partner with departments of information technology, business, economics, data science, and public administration.

Joint programs, dual degrees, and collaborative research will produce professionals who are fluent in multiple disciplines — able to translate between law, code, and commerce.

5. Countryside Innovation Labs: Expanding the Map of Opportunity

The fifth and, perhaps, most personal is the establishment of Countryside Innovation Labs.

I have always believed that innovation should not end where the highways do.

In my years working on digital transformation with local governments, I’ve seen the immense potential of the countryside — talented youth, emerging entrepreneurs, creative communities — waiting only for access, mentorship, and legal guidance.

By linking local law schools with LGUs, MSMEs, and ICT councils, we can create regional innovation ecosystems that ensure development is truly inclusive.

These labs could help localities:

- Draft innovation-friendly ordinances;

- Develop startup support frameworks;

- Strengthen data protection and cybersecurity measures; and

- Build capacity for digital governance.

When law schools anchor innovation in local governance, they don’t just produce graduates — they produce community catalysts.

As UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report (2023) beautifully states, “Digital transformation must be guided by human transformation.”

That is precisely the role of legal education — to serve as the bridge between the fastest technologies and the deepest human values.

This is the vision — a Philippines where legal education fuels innovation, innovation drives inclusion, and inclusion defines justice.

Let us teach the nation to be digitally humane — by teaching future lawyers that technology is not beyond the reach of law, and that justice must be as connected as the world it seeks to govern.

Because when education leads innovation, and the law safeguards inclusion, the result is not just a connected nation — It is a compassionate, digitally just nation.

We will have transformed legal education from being a profession’s foundation into a nation’s innovation engine.

And that begins in our classrooms — where we are not only teaching law, but shaping the moral and intellectual foundations of a digital Philippines.

Thank you for listening.

Leave a comment