Why Integrity Remains the Missing Link

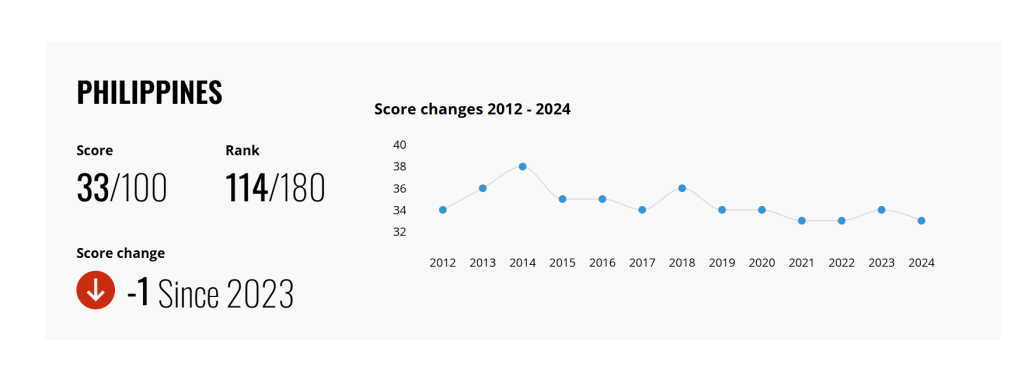

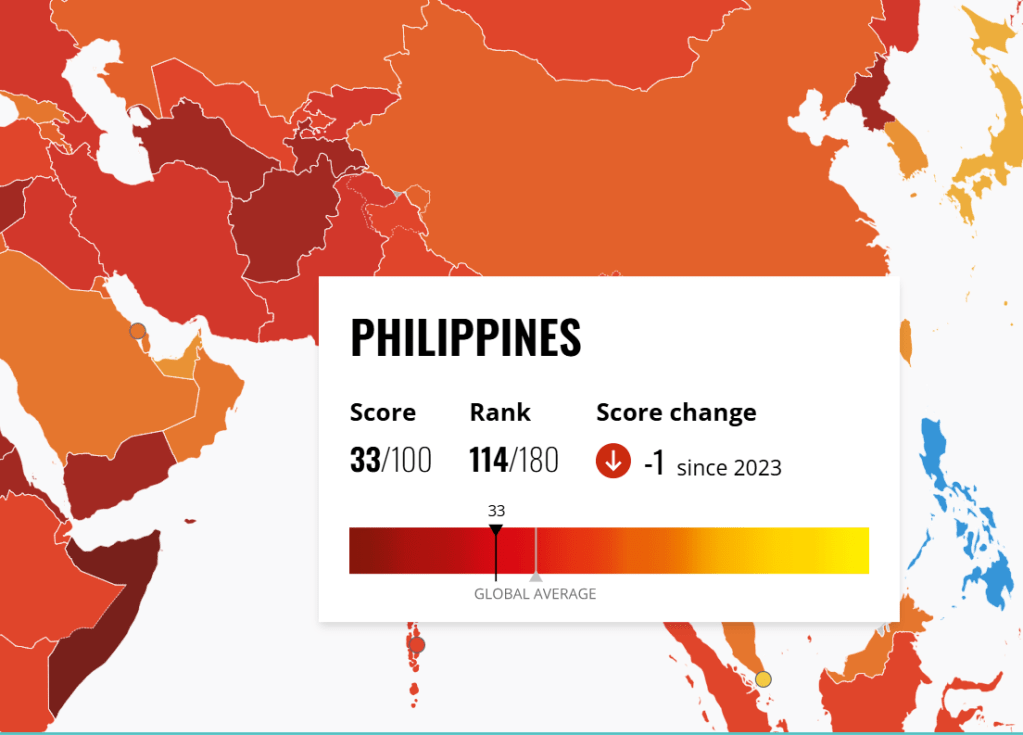

Every year, Transparency International releases the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI)—a global benchmark that does not simply rank nations, but reflects the way governance is experienced. The CPI 2024, released in February 2025, once again delivers a sobering message for the Philippines: we remain stuck in a cycle of weak integrity, institutional distrust, and missed opportunities.

The Philippines scored 33 out of 100, ranking 114th out of 180 countries. This is below the Asia-Pacific regional average of 44, and far behind our neighbors who have managed to build stronger reputations for governance.

Some dismiss the CPI as “just perception.” But perception, in governance, is power. It shapes whether citizens trust their leaders, whether investors take risks, whether partners extend support. A country may build roads and bridges, but without integrity, these can easily become monuments to wasted opportunity.

As someone who has long championed inclusive growth, countryside development, and innovation ecosystems, I see corruption not as an abstract issue but as the single most corrosive barrier to genuine progress. It bleeds public funds, distorts priorities, and erodes hope. And when hope is lost, cynicism takes its place—a dangerous condition for any democracy.

What the CPI Measures—and Why It Matters

The CPI is built on 13 independent data sources, including assessments from the World Bank, World Economic Forum, and other regional development institutions. It is not about catching every peso lost or every official bribed—that is impossible. Instead, it measures how corruption is perceived and experienced by those who interact with systems: businesses, experts, and civil society.

It captures dimensions such as:

- Whether public funds are diverted for private gain.

- Whether officials use their position for personal benefit.

- Whether courts and institutions are independent enough to enforce accountability.

- Whether anti-corruption laws exist only on paper or in practice.

- Whether the media and civil society can investigate freely.

- Whether procurement and budget processes are transparent.

In this sense, CPI is less about statistics and more about trust in systems. A low score signals that citizens, businesses, and observers believe rules can be bent, enforcement is selective, and corruption is normalized.

Southeast Asia’s Integrity Spectrum

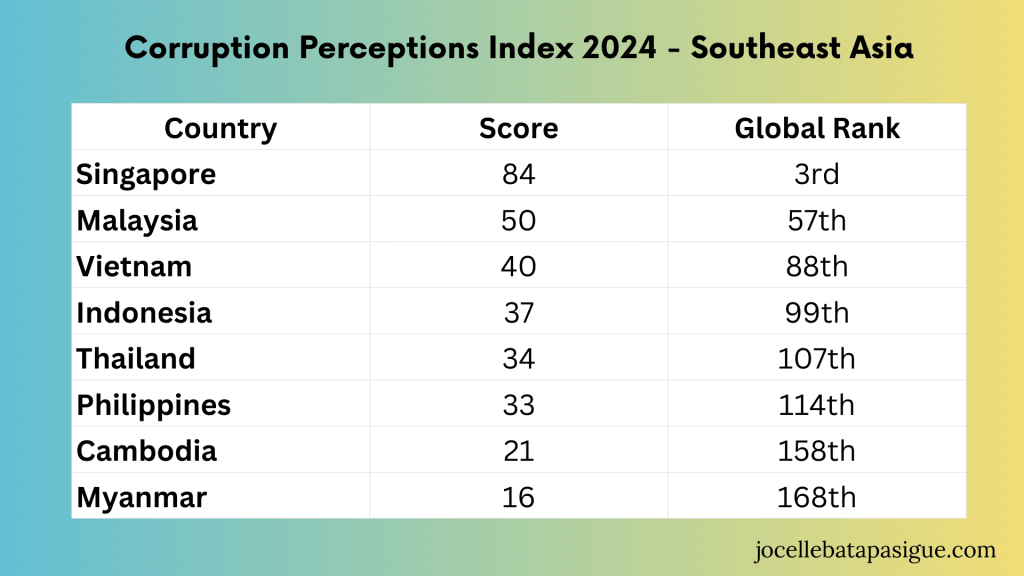

The 2024 CPI reveals a spectrum of governance across Southeast Asia.

At the top is Singapore (84/100, 3rd globally)—proof that corruption is not inevitable in Asia. Its professional bureaucracy, efficient enforcement, and consistent rule of law have built a culture where corruption is the exception, not the rule.

Malaysia (50/100, 57th) sits above the regional average, managing to retain moderate credibility despite past scandals like 1MDB. Incremental reforms continue to sustain some investor confidence.

Vietnam (40/100, 88th) and Indonesia (37/100, 99th) have undertaken highly publicized anti-corruption drives. Citizens see these as imperfect but meaningful attempts to break cycles of impunity.

Thailand (34/100, 107th) and the Philippines (33/100, 114th) remain nearly tied in the lower ranks—struggling with entrenched patronage and institutional fragility.

At the bottom, Cambodia (21/100, 158th) and Myanmar (16/100, 168th) remain captured by systemic corruption, where reforms are either cosmetic or impossible under weak governance.

While Southeast Asia’s economies grow, integrity does not always keep pace. This divergence creates both risks and lessons.

The Philippines’ CPI Record: A Decade of Stagnation

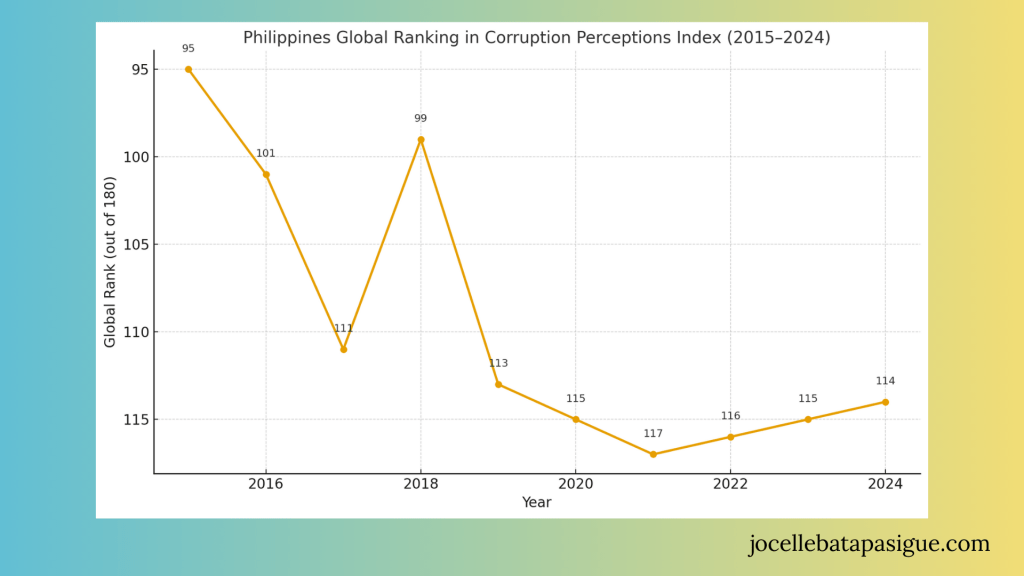

Tracing our CPI scores over the last decade shows troubling consistency in underperformance:

- 2015: 35/100, ranked 95th

- 2016: 35/100, ranked 101st

- 2017: 34/100, ranked 111th

- 2018: 36/100, ranked 99th

- 2019: 34/100, ranked 113th

- 2020: 34/100, ranked 115th

- 2021: ~33/100, around 117th

- 2022: ~33/100, around 116th

- 2023: ~32/100, around 115th

- 2024: 33/100, ranked 114th

One can see how fleeting improvements are swallowed by regression. The 2018 high point at 99th place was not sustained. Instead, the country slid back into the 110s, unable to escape the gravitational pull of weak institutions.

This stagnation signals a deeper truth: reforms have often been announced but not enforced, structures created but undermined, rules passed but selectively applied. Citizens sense this gap between rhetoric and reality, and the CPI reflects that disillusionment.

Why Low CPI Scores Hurt the Filipino People

A low CPI is not just an embarrassment on paper—it has real consequences.

First, it robs development. Every peso lost to corruption is a school unbuilt, a hospital unequipped, a farmer unsupported. It means fewer digital hubs in rural areas, fewer scholarships for youth, fewer opportunities for innovation to reach the countryside.

Second, it deters investors. International businesses scan governance indices before investing. A country with low integrity signals high risk. Investors worry about hidden costs, opaque processes, and unpredictable enforcement. That means fewer jobs, less capital, and slower economic growth.

Third, it erodes trust. When corruption becomes normalized, citizens disengage. They stop reporting abuses, stop expecting justice, stop participating in civic life. This cynicism corrodes democracy, because governance without trust is like a house without foundation.

Fourth, it worsens crises. In pandemics or disasters, corruption becomes deadly. Relief funds disappear, procurement is rigged, and aid fails to reach those who need it most. Transparency is not just about efficiency—it is about survival.

Why the Philippines Struggles with Corruption: Five Structural Barriers

Corruption in the Philippines is not merely a matter of individual greed—it is a product of structural conditions that allow it to persist. Institutions are weakened, processes remain opaque, and cultural norms often tolerate what should be unacceptable. To understand why the country has consistently ranked in the lower tiers of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for over a decade, we must confront five enduring barriers.

Weak Enforcement

Oversight bodies exist, but many lack the independence, resources, or authority to act decisively. The national anti-corruption office, tasked with investigating and prosecuting corrupt officials, handles thousands of cases annually but operates with limited staff and budget. In 2022, it reported fewer than 800 authorized positions, with only a few hundred investigators covering the entire country—a scale mismatch that undermines effectiveness. Moreover, when leadership appointments are influenced by political patronage, institutional autonomy is compromised. Without genuine independence, enforcement becomes symbolic rather than substantive, eroding public trust in accountability mechanisms.

Patronage Politics

Philippine governance remains heavily shaped by patronage, where loyalty is often rewarded over competence. Appointments to regulatory bodies, government corporations, and law enforcement agencies are frequently distributed to political allies, weakening professionalism and reform momentum. A 2019 policy study found that approximately 70% of national legislators belonged to political dynasties, reinforcing power concentration and limiting impartial decision-making. This system discourages merit-based governance and fosters environments where accountability is conditional, not institutional.

Opaque Procurement

Government procurement remains one of the most corruption-prone sectors. While the Government Procurement Reform Act (RA 9184) introduced safeguards, loopholes persist. “Tailor-made” bidding processes allow favored contractors to win, and auditing often occurs too late to prevent misuse. The national audit commission has repeatedly flagged billions in questionable transactions, including high-profile cases involving overpriced pandemic supplies awarded to firms with political connections and minimal operational capacity. These incidents reinforce public perception that procurement is driven more by influence than by efficiency or integrity.

Judicial Delays

Even when corruption cases reach the courts, justice is often delayed. The country’s anti-graft court has long been criticized for multi-year proceedings, with some cases stretching across decades. As of mid-2023, the court reported 1,571 unresolved cases—a 42-year low, yet still indicative of systemic backlog. While this reflects some progress, the pace of resolution remains slow enough to undermine the deterrent effect of prosecution. When accountability is delayed, its impact is diluted, and public confidence in the judiciary suffers.

Cultural Normalization

Corruption in the Philippines is not only systemic—it is also cultural. Practices like lagayan (grease money) and palakasan (influence-peddling) are often seen as practical shortcuts to navigate bureaucracy, secure permits, or expedite services. A 2020 national survey revealed that 65% of Filipinos believed “most or all” officials were corrupt, and many admitted to paying bribes themselves. This normalization creates a vicious cycle: citizens expect corruption, participate in it reluctantly, and then feel powerless to challenge it. The result is a culture of resignation rather than resistance.

Breaking the Cycle

These five barriers—weak enforcement, patronage politics, opaque procurement, judicial delays, and cultural normalization—reinforce one another. Weak enforcement enables patronage. Opaque procurement feeds judicial backlogs. Cultural acceptance discourages civic pressure for reform.

If the Philippines is to rise in global integrity rankings, these structural weaknesses must be addressed in tandem. Enforcement must be empowered with autonomy and resources. Political systems must prioritize merit over loyalty. Procurement must be transparent and accountable. Courts must deliver timely justice. And cultural norms must shift from acceptance to active resistance.

Only then can integrity move from rhetoric to reality—and from aspiration to institutional habit.

In my perspective, these structural failures are not only legal but also cultural and ethical. A society that tolerates “small” corruption—like grease money for permits—eventually normalizes “big” corruption in billion-peso contracts.

Lessons in Integrity: What the Philippines Can Learn from Global Models

When people say corruption is inevitable in Asia, I point to Singapore. Here is proof that integrity is not about culture or geography—it is about institutions and political will. For decades, Singapore has consistently ranked among the top in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), scoring 84/100 in 2024 and placing third globally. This success rests on strong, independent institutions and consistent enforcement. The Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) operates directly under the Prime Minister’s office but with independence safeguarded by law. Its mandate is clear: investigate all cases, regardless of rank. Over time, the certainty of enforcement created a culture where corruption is not worth the risk. Trust in government followed, and Singapore transformed itself from a struggling postcolonial state into a global financial hub.

Indonesia, while not at Singapore’s level, once offered a compelling lesson through the Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (KPK), its Corruption Eradication Commission. Established in 2003, the KPK quickly gained credibility for investigating high-ranking officials, business elites, and even members of parliament. In 2015, it began investigating the Speaker of Parliament in a high-profile graft case that culminated in formal charges in 2017, sending a clear message that no one was above the law. Public backing for the KPK was immense; surveys showed it consistently ranked as one of the most trusted institutions in Indonesia. Unfortunately, 2019 legislative changes have clipped its powers, showing how fragile reform can be without sustained political commitment. Still, the KPK demonstrated that an empowered and independent watchdog can dramatically shift perceptions in a short span of time.

Vietnam’s approach has been different but equally instructive. Under its “blazing furnace” anti-corruption campaign launched in 2016, the Communist Party initiated hundreds of investigations, some targeting senior officials. In 2023 alone, Vietnam disciplined over 24,000 party members, including ministers and deputy prime ministers, for corruption and mismanagement. Critics argue that the campaign is selective and politically motivated, but its visibility has shaped public perception. Ordinary citizens saw once-untouchable leaders face consequences, reinforcing the idea that accountability—even if partial—is possible.

Rwanda offers a striking case outside Asia. Despite being one of the poorest nations in the 1990s, Rwanda has steadily improved governance by embedding integrity into procurement processes. Its National Tender Board oversees all major contracts, and independent reviews are mandatory to prevent collusion. According to the World Bank, these reforms contributed to Rwanda consistently ranking as one of the least corrupt countries in Africa, with a CPI score of 53/100 in 2024, higher than the global average. By making procurement transparent and accountable, Rwanda not only reduced leakages but also rebuilt public trust in a post-conflict society.

Finally, Ukraine’s Prozorro e-procurement platform offers a powerful digital solution. Launched in 2016 under the principle “everyone sees everything,” Prozorro publishes all procurement data online—from tenders and bidders to final contracts. Civil society, journalists, and even competitors can scrutinize transactions. The results have been remarkable: according to Transparency International Ukraine, Prozorro saved the government an estimated $6 billion in its first five years. Even amid war, Ukraine has maintained the system, showing how digital tools can embed transparency as a default rather than an exception.

Each of these models demonstrates that corruption is not destiny. Strong institutions, independent oversight, visible enforcement, transparent procurement, and digital innovation are powerful antidotes. The Philippines can draw from these lessons, tailoring them to our own context. After all, corruption thrives where citizens believe nothing can change. These examples prove that change is not only possible—it is happening, but it requires both political will and systemic innovation.

Why Integrity is a Competitiveness Issue

Beyond morality, integrity is now a global competitiveness factor.

The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report (2025) highlights trust in institutions as a condition for digital and green transitions. The OECD’s call for data-driven public sectors stresses that transparency is central to efficient governance. The ITU’s digital development studies show that connectivity and innovation cannot thrive without trust in public systems.

For the Philippines, staying at 33/100 on the CPI means not only losing aid or investor confidence—it means missing the digital future. No amount of infrastructure or investment can substitute for trust.

Rebuilding Integrity: A Philippine Agenda

The path forward requires more than rhetoric. For as long as I can remember, we Filipinos have heard endless speeches and promises about fighting corruption. Every administration comes with its own slogans, its own anti-corruption campaigns. And yet, year after year, our scores on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) remain stuck in the 30s.

For me, this is not simply about rankings. It is about the lived reality of citizens—parents who see classrooms delayed, farmers whose subsidies disappear, communities waiting for clinics that never get built. It is about the daily frustration of navigating a system where shortcuts and bribes are often treated as normal.

That is why I believe the way forward is not about rhetoric. It is about deep systemic change. We cannot paper over this crisis with slogans. We must confront it with reforms that cut to the heart of our institutions and our culture.

Shielding Oversight Bodies from Politics

At the center of any real change are independent oversight bodies. Without them, integrity collapses. The sad truth is that in the Philippines, many of our institutions meant to guard against corruption often end up vulnerable to politics.

I have seen how oversight bodies lose credibility when their leaders are handpicked for loyalty rather than integrity, when cases are stalled for political convenience, or when whistleblowers are silenced instead of protected. If we are serious, we must shield these institutions from political interference.

That means secure tenure, transparent appointments, budgetary independence, and systems that make them accountable not to politicians but to the people. I have long admired how countries like Singapore managed to insulate their integrity systems from partisan influence. We can do the same—if we have the courage.

Radical Transparency in Procurement and Budgeting

I have always believed that corruption thrives in the shadows. Nowhere is this more evident than in procurement and budgeting, where billions of pesos flow with little citizen visibility.

The solution is radical transparency. We must move beyond token disclosures and adopt open contracting data standards so that every Filipino can see how funds are spent. Who bid? Who won? Was the project delivered? Was it worth the cost?

Other countries have shown the way. Ukraine’s Prozorro system works under the principle that “everyone sees everything.” Imagine if, in the Philippines, every barangay project was fully traceable online—with photos, contracts, and expenditures. Such openness would not only deter theft but would also rebuild trust.

Transparency is not just a technical reform—it is a cultural shift. It tells citizens: “We have nothing to hide. This is your money. Come and see where it goes.”

Empowering Civil Society and Media

I also know that no government can police itself alone. Civil society and the media are our partners in accountability. Investigative journalists, NGOs, watchdogs, and even local communities have played crucial roles in exposing wrongdoing.

Yet, too often, these voices are dismissed, threatened, or harassed. That is not only unjust—it is self-defeating. Silencing watchdogs weakens democracy and emboldens corruption.

I have always maintained that citizens should not be mere spectators. They must be co-authors of governance. Empowering civil society means protecting press freedom, supporting investigative journalism, and creating genuine space for NGOs and citizen groups to monitor public funds. Accountability is strongest when it is collective.

Judicial Reform: Breaking the Cycle of Impunity

Perhaps the most frustrating part of our anti-corruption struggle is how long cases take. We all know the phrase “justice delayed is justice denied.” But here, it is more than a phrase—it is reality.

Cases drag on for decades. By the time a ruling is reached, evidence is lost, witnesses are gone, or the public has already moved on. Worse, the accused often return to power as if nothing happened. This cycle of impunity erodes any sense of accountability.

If we are serious, we need specialized courts for corruption cases, more efficient procedures, and stronger protection for judges who choose integrity over influence. Other countries have shown that speed and fairness can go together. We owe it to our people to prove that accountability in the Philippines can also be swift and certain.

Education for Integrity: Planting Seeds Early

But reform cannot stop at institutions. We must reshape culture. Corruption has become so normalized in our society that many treat it as a fact of life. Changing this requires starting young.

In my years as an educator, I have seen how deeply values are formed in classrooms. If children grow up seeing dishonesty as acceptable—whether in exams, in small favors, or in local governance—they carry that into adulthood. But if they grow up with lessons and role models that emphasize integrity, service, and fairness, they become the leaders and citizens who demand better.

That is why I believe education for integrity must begin early. Ethics and civic responsibility should not be token subjects but woven into every aspect of schooling. Teachers themselves must embody transparency. Communities must reward honesty. Over time, this can change not only behavior but also expectations.

Restoring Hope

For me, the ultimate goal of fighting corruption is not punishment—it is restoration. We must restore hope.

Hope that when taxes are paid, they return as roads, clinics, and classrooms—not as foreign bank accounts and private mansions.

Hope that young people can succeed based on merit, not connections.

Hope that justice can be served, and leaders can be held accountable.

Corruption does not only steal money—it steals faith in the future. And without faith, no democracy can thrive.

That is why I refuse to see the fight against corruption as naïve. To me, it is the most pragmatic struggle of all. A nation cannot dream of prosperity, innovation, or inclusion if its own systems are hollowed out by graft.

Choosing Integrity

The road to integrity is long, and it will not be easy. But I remain convinced that it is possible. Shield oversight bodies. Make procurement transparent. Empower civil society. Reform the courts. Teach integrity early. These are not lofty ideals—they are practical reforms we can and must pursue.

The truth is that we do not lack knowledge. We know what works. What we lack is consistency and political will.

Still, I choose to believe in the possibility of change. Because every small act of integrity creates ripples. Every case resolved, every project made transparent, every classroom where honesty is taught—these are victories. And victories build momentum.

The CPI may tell us where we stand today. But it does not decide our future. Integrity is not destiny—it is choice. And I believe we Filipinos, weary as we may be, still have the strength to choose hope, choose fairness, and choose integrity.

Breaking the Cycle

The CPI 2024 reminds us that corruption is not just a statistic. It is the everyday reality of broken trust and stolen opportunities. But it is not destiny. Countries have shown that determined reform, transparency, and leadership can change trajectories within a decade.

For the Philippines, the challenge is not lack of knowledge. It is lack of courage. We know what needs to be done—independence of institutions, transparency of systems, accountability of leaders. What remains is the collective will to do it.

Corruption is the enemy of innovation, inclusion, and progress. To rise in the CPI is not simply to look good on paper—it is to ensure that our people, especially in the countryside, finally receive the opportunities they deserve.

The choice is ours – to remain trapped in stagnation, or to climb, step by step, toward integrity. The CPI is not a sentence—it is an invitation. An invitation to build a Philippines where honesty is strength, transparency is culture, and governance is truly for the people.

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is published annually by Transparency International, a global non-governmental organization dedicated to combating corruption and promoting transparency in public institutions. Established in 1993, Transparency International launched the CPI in 1995 to rank countries based on perceived levels of public sector corruption, using expert assessments and business surveys. Today, the CPI covers 180 countries and territories, scoring them on a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean), and remains one of the most widely cited benchmarks for global governance and institutional integrity.

Leave a comment